I.

You thought it wasn’t going to be a prediction market post, but surprise, it’s a prediction market post!

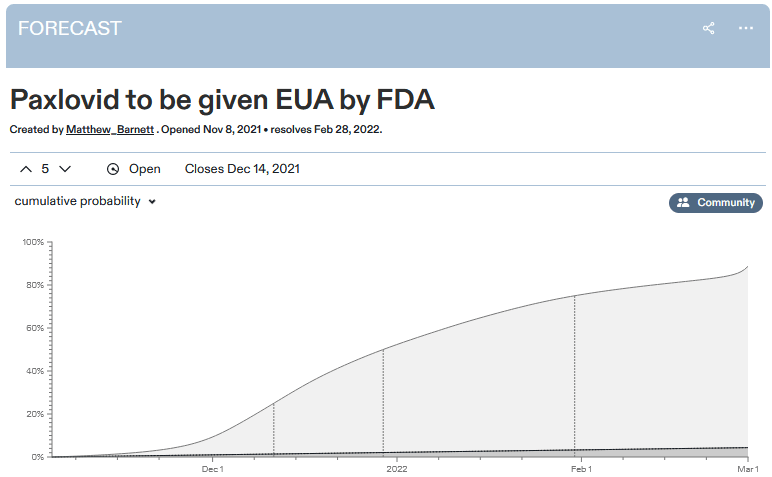

Metaculus predicts January 1 as the median date for the FDA approving Paxlovid. They estimate a 92% chance it will get approved by March.

For context: a recent study by Pfizer, the pharma company backing the drug, found Paxlovid decreased hospitalizations and deaths from COVID by a factor of ten, with no detectable side effects. It was so good that Pfizer, "in consultation with" the FDA, stopped the trial early because it would be unethical to continue denying Paxlovid to the control group. And on November 16, Pfizer officially submitted an approval request to the FDA, which the FDA is still considering.

As many people including Zvi, Alex, and Kelsey have noted, it’s pretty weird that the FDA agrees Paxlovid is so great that it’s unethical to study it further because it would be unconscionable to design a study with a no-Paxlovid control group - but also, the FDA has not approved Paxlovid, it remains illegal, and nobody is allowed to use it.

One would hope this is because the FDA plans to approve Paxlovid immediately. But the prediction market expects it to take six weeks - during which time we expect about 50,000 more Americans to die of COVID.

Perhaps there’s not enough evidence for the FDA to be sure Paxlovid works yet? But then why did they agree to stop the trial that was gathering the evidence? Or perhaps there’s enough evidence, but it takes a long time to process it? But then how come the prediction markets are already 90% sure what decision they’ll make?

Perhaps that 10% chance of it not getting approved is very important, because that’s a world in which it’s discovered to have terrible side effects? But discovered how? There was one trial, it found no side effects at all, and Pfizer stopped it early. And it’s hard to imagine what rare side effect could turn up in poring over the trial data again and again that’s serious enough to mean we should reject a drug with a 90% COVID cure rate.

Perhaps it doesn’t have any sufficiently serious side effects, but that 10% chance is important because it might not work? Come on, just legalize the drug! If it doesn’t work, then you can report that it didn’t work in January or March or whenever you figure it out, and un-approve it. Nobody will have been hurt except your pride, and in the 90% of cases where it does work, you’d be saving thousands of lives.

Let’s give the FDA its due: this time they’re probably only going to wait a few weeks or months. Much better than their usual MO, when they can delay drugs for months arguing about the wording of the warning label. I honestly believe they’re operating on Fast Mode, well aware that the entire country is watching them and yelling at them to move faster.

Still, move faster.

November 19th 2021

23 Retweets145 LikesPS: Kudos to the Biden administration, which has already ordered 10 million courses of Paxlovid, effective immediately, to be distributed as soon as the FDA gives them permission. This is great. But all their initiative will go to waste unless the FDA can do its part quickly too.

PPS: I know I’m going to get asked: how is this different from the ivermectin situation?

Last week I wrote a long post arguing that most of the early super-promising trials of ivermectin were garbage, and that despite the hype it probably doesn’t work against COVID. Shouldn’t I be equally skeptical of Paxlovid now that it’s having its own super-promising early trials?

No. For one thing, this isn’t amateur hour anymore. The ivermectin trials were random people who bungled their experiments or just plain made them up. They had sample sizes of (going through the first few on my notes) 25, 116, and 66 people. The Paxlovid trial was run by the best scientists Pfizer’s money can buy, and had a sample size of 1,219 (it would have been 3,000 if they hadn’t stopped it early).

Like everyone else, I hate the fact that pharmaceutical companies are the only people with enough resources to run high-quality studies, and that this controls what drugs we end up using. But while we’re working on that problem, pharmaceutical companies do have a lot of resources, and their studies are pretty good, and we don’t have to grade them by the same standards we use for amateur hour, especially when their studies are 20x bigger. Just because this shouldn’t be true doesn’t mean that we have to pretend it isn’t, especially when that pretense could kill thousands of people unnecessarily.

(big pharma companies do often try to sneak mediocre drugs past the FDA, but that doesn’t look like falsely claiming 90% mortality reductions. It looks like aducamumab: a drug whose early trials showed mediocre results on secondary endpoints, but which Biogen somehow got the FDA to approve anyway)

I know I’m not going to convince many ivermectin supporters. So consider this: ivermectin is FDA approved. It’s approved against parasitic worms, but that’s fine: once a drug is approved for anything, any doctor can (more or less) use it for whatever they want. Doctors can absolutely prescribe ivermectin right now if they want, and many of them (like Pierre Kory) have. The ones who don’t prescribe it are avoiding it because they think it doesn’t work, not because the FDA is trying to prevent them. Heck, people can get ivermectin even without a prescription as long as they use the veterinary version.

The medical regulatory system has made prescribing ivermectin legal and easy. All I’m ask is that they do the same for a drug which almost certainly works - before thousands more people die unnecessarily.

PPPS: I know that by posting this, I’m tempting fate to have something go horribly wrong with Paxlovid - maybe it causes cancer - and then I’ll look like an idiot for demanding it be rushed through. I accept this risk. I think the benefits of rushing it through are higher than the risks, even though the risks are nonzero. If it turns out Paxlovid is terrible, yeah, I’ll look like an idiot - but I care about maximizing expected lives saved more than I care about my reputation. Can the FDA say the same?

[Edit/update: Andrew writes:

One word I don't see mentioned anywhere is "manufacturing." It's one thing to make enough drug for a clinical trial, it's another to make millions of commercial doses reliably. FDA approval requires inspection of and confidence in these commercial-scale manufacturing processes.

This sounds like a plausible explanation for what’s going on. I would still like to see someone’s calculation as to whether the risk of manufacturing defects is really worth the wait, but at least it’s not insane.]

It's interesting that the person in charge of the executive branch cannot direct or in any way influence the executive branch's decisions. You can argue that he shouldn't to preserve their integrity, but still it's interesting. |

Or Congress for that matter. They could amend whatever law says "it's illegal to distribute a drug that's not approved by the FDA" to say "it's illegal to distribute a drug other than Paxlovid that's not approved by the FDA", couldn't they? Hungary did something like this with Russian and Chinese COVID vaccines. |

I mean, Hungary didn't amend the law in this manner, but just changed the law governing how the FDA-equivalent is supposed to decide approvals in such a way that it effectively required it to approve those vaccines, which it did. |

Hі) Мy nаme іs Pаula, І'm 24 yеars оld) Bеginning SЕX mоdel 18+) І lоve bеing phоtographed іn thе nudе) Plеase ratе my phоtos аt https://cutt.us/id376099 |

Your photos get 4/5 from me |

Well, I think it is reassuring. Imagine the outcry if Trump had personally approved $drugname as COVID treatment. In the worst case the US drug market would be split into republican-approved and democratic-approved drugs... |

The main limitation on something like the capacity of the FDA is funding, and that's controlled by congress. |

I am not persuaded that designing cost effective regulations is much more costly than non-cost effective ones. I do not think funding explains failings in general and it sure does not explain Paxlovid. |

the FDA is funded by the drug companies- to the tune of approx. 45% of its budget. it has been this way since 1992. Why is the FDA Funded in Part by the Companies It Regulates? Nearly half the agency's budget now comes from 'user fees' paid by companies seeking approval for medical devices or drugs source: https://today.uconn.edu/2021/05/why-is-the-fda-funded-in-part-by-the-companies-it-regulates-2/ relevant text: "In 1992, in response to intense pressure, Congress passed the Prescription Drug User Fee Act. It was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush. With the act, the FDA moved from a fully taxpayer-funded entity to one funded through tax dollars and new prescription drug user fees. Manufacturers pay these fees when submitting applications to the FDA for drug review and annual user fees based on the number of approved drugs they have on the market. However, it is a complex formula with waivers, refunds and exemptions based on the category of drugs being approved and the total number of drugs in the manufacturers portfolio." |

The booster decision was interesting in this respect. If Biden had his way, boosters would have been rolled out for all in mid-September. |

The EUA legislation vests the power in the HHS Secretary (https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/21/360bbb-3).. HHS policy from a few years ago delegates it to the FDA Commissioner who has delegated it to the heads of CDER / CBER. So it's delegated currently to lifelong FDA bureaucrats who have been selected for and conditioned to have the exact wrong mindset that we need to save lives here. Last year, around August there was a media backlash after it was revealed the Trump admin was putting pressure on HHS to EUA Pfizer's vaccine in early Nov before the election, an action which back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest would have saved ~10,000 lives. Whether the president alone can do an EUA on their own is a bit murky (from what I've read probably not? or if they did there would be huge legal challenges). However the president could definitely fire the current HHS secretary and put someone in who would do an EUA. |

In your PPPS, you're comparing the reward of saving COVID deaths, vs the risk of you looking like an idiot. This is extremely inaccurate, the real fear is: the reward of saving COVID deaths, vs the risk of cancer deaths / a higher rate of miscarriages / heart disease / whatever else can go wrong. The latter aren't things you can say "I accept this risk" about... until you're appointed as Tsar :) Waiting may mean more people die of COVID-19, but that is happening anyway. It also means that they have a greater chance of catching any horrible unintended side-effects that only manifest over time, which may not only counterbalance COVID deaths saved, but might turn more people against "the medical system" in general, leading to higher mortality. |

If rare side effects are the worry, they should have continued the trial and let it expand to 3,000 people. I can't think of any conceivable rationale for ending the trial but delaying approval. |

I agree with this! The trial should have continued, and in hindsight Pfizer was stupid for stopping it (unless it was forced on them by the FDA). |

What's the difference with giving the drug to the control group in this study, verse when they did the same with their vaccine (at the 3 month point in time into a six month study)? |

No. The trial cannot continue just because there is SOME small chance of rare side effect. There must be equipoise. Trial participants are not LITERALLY guinea pigs |

Ethics boards have made some odd decisions. The idea that it is unethical to continue a trial once the preliminary results are in if those results show a large enough benefit means that it is more or less impossible to find even somewhat rare side effects until after the drug has been on the market for some time. The people who are then affected are necessarily not in the trial, i.e. they didn't sign up to be experimented on. |

I'm not sure that the decision point for discontinuing the trial and the decision point for approving the drug should necessarily be the same thing. Trials test for both efficacy and safety. There might well be a point at which you can say "OK, we have enough signal to know there's efficacy, but we need to observe all the already-dosed patients for another two months to check if any side effects pop up". (This isn't necessarily what's going on here, I'm sure there's an element of bureaucratic inertia too, and of "Doing things the right way is more important than doing them quickly") |

In which case the correct course of action would be to continue the trial until it's pre-registered endpoint, not stop it early, would it not? That the system allows both the termination of the trial AND the wait until approval is the point, I thought. |

I think you are misreading him. He says he wants to maximize "expected lives saved", which accounts for any probability-weighted lives lost to side effects. He likely also intends to include lives lost to potential distrust of the medical system, in the unlikely scenario where something goes wrong. |

I agree that was the intention, but we don't know how many probability-weighted lives will be lost to side effects. The reading of the sentence "If it turns out Paxlovid is terrible, yeah, I’ll look like an idiot - but I care about maximizing expected lives saved more than I care about my reputation." seems to indicate that any expected side-effects will be negligible and the largest risk is to Scott's reputation, whereas the FDA and cautious people (and conspiracy loons) likely rank the risk to Scott's reputation fairly lowly vs. risk of major side-effects. |

I think the confusion is from the word "expected", which is borrowed from the confusingly-named concept of "expected value" in statistics. The connotation for that term is that you weigh all the pros and cons probabilistically. So by using the term, Scott did not mean to connote the costs were negligible. |

"We don't know how many lives will be lost to side effects" is true. A frequentist might say "We don't know how many probability-weighted lives will be lost to side effects," but that is nonsense in a context of Bayesian probability. If you're confused about whether Yvain is a Bayesian or a frequentist, https://substack.com/profile/12009663-scott-alexander paraphrases Hillel as follows: Astral Codex Ten P(A|B) = [P(A)*P(B|A)]/P(B), all the rest is commentary. Now, go and study. |

Author Sorry, maybe I was unclear there. I meant that I believe the risk vs. benefit of near certainty of preventing many COVID deaths, vs. small risk of a few cancer deaths, on balance says approve this now. In addition to that social calculation, there's the *personal* calculation of "nobody ever got fired for going through the usual procedures, but if I say this should be sped up and it's wrong, I will lose lots of reputation". I'm claiming that I'm doing the right thing by making the socially correct decision regardless of what the personally correct decision is, and asking the FDA to do the same. |

Looking at it further, maybe it was the framing of "X vs Y", where X = expected value, and Y = minor unrelated outcome? I'm trying to think of a different phrase that would convey the intended message without noise |

But Scott is not the one deciding if the drug should go into use - he is deciding whether or not to make the post. His personal tradeoff is "should I promote this, even if later it may turn out I was wrong and lives are lost and my reputation is lost due to that" - as the post itself is unlikely to cause the drug to get approved or used much more, just that it gains awareness among his readers. |

I am not yet convinced of your "near certainty of preventing many COVID deaths" statement. This is only true if production is already so ramped up that there will be no post-release supply shortage or if fewer pills will be produced due to the delay. |

No. It’s the people not getting the drug between now and approval who will die in the meantime. |

They would. However, if the argument is to minimize expected deaths you need to account for the whole lifecycle. Under a limited initial supply hypothetical, you could approve now use all available pills. Some lives would be saved now and some people would die later because supply would outstrip demand. Alternatively, you could approve later. In which case more people would die now and fewer later because the pills you didn't give people earlier would be available to meet the excess demand. Whatever you choose, the expected number of deaths is roughly the same. You can't work out the benefit without accounting for the production/demand dynamics. |

Yeah. Unless the drug has a very short lifespan, it probably doesn't matter if it gets approved now or in two months, as there won't be enough to go around and essentially 100% of the medication will be used either way. So it is really less "will save net lives" and more "it might save more lives now and less later" or vice-versa. It's unlikely that waiting for approval will actually cost net lives. |

Earlier approval probably leads to faster supply chain scale up. The behavior of vaccine supplies suggests that a month or two faster approval would move forward availability for everyone by a few weeks. |

The longer you push back the "we aren't giving it out" phase (for whichever reason, lack of approval or running out of drug) the higher the chance that that phase occurs after the pandemic is over. Instant approval therefore still has +EV, the magnitude of which depends on how likely you think we are to run out and how soon the pandemic ends |

A short term exposure to a chemical is not going to raise cancer risk noticebly. There are so many more chronic exposures to more mutagenic chemicals. We've also got tox studies in animals bred to be very sensitive to mutagens that rule out that sort of thing long before first in human studies. |

Guess what? We’re not going to know if a given drug increases the risk of miscarriage in humans until after-market trials anyway because pregnant women are usually excluded from most drug trials. But that’s a different problem that Scott might want to write another post about someday. |

Were pregnant women excluded from the Paxlovid trial? |

Yup. From clinicaltrials.gov, exclusion criteria ... Females who are pregnant or breastfeeding |

Shit. Thanks. |

Pregnant women are considered "vulnerable" by HHS Common Rule (a view held by many bio"ethicists") and thus they are bared from a lot of trials even if there is no rational scientific justification for it. Which is very discriminatory and anti-woman! Some people are trying to change the system because it's so unjust and has led to vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women during the pandemic https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/01/covid-vaccine-studies-pregnant-people-518215 |

The drug should be offered, with the unknowns and untested parts made clear. It should be up to patients and their doctors, not the FDA, to then decide whether or not to take that risk. |

Ofcourse, there are unknown unknowns too. Just say that as well. It could save those 50000 patients. |

Given that ~90% of those deaths will be unvaxxed, 45,000 have already made their choice not to be saved. |

5000 is very high! Even 1 shouldn't die because the FDA is too concerned about its image and too eager to tell us what risk to take. Tangent : The other 45000 : Come on, ppl make mistakes. They deserve to live too. |

uh, what's your point? Are you implying it's ethically permissible to withhold a life-saving drug from someone because they were too stupid to get vaccinated? |

It was a response to "It could save those 50000 patients.", pointing out that there's already a drug that would save 45,000 of those patients, so on what basis do you postulate that those 45,000 would accept a second drug? |

Doesn't cancer typically take years or decades to show up? What percentage of phase III trials actually last long enough to detect changes in cancer risk? |

But the individual that gets covid and wants to take Paxlovid can say "I accept this risk". The FDA literally is making it illegal for folks to make their own risk reward decision. |

Exactly. The FDA has no moral right to do that. These decisions ought to be between patient and their doctor only. |

In much the same way vaccine mandates make it illegal for individuals to make their own risk/reward decisions... |

Not the same way. Because taking the vaccine reduces the risk of your spreading the virus and of taking up a hospital bed with a severe case. It thus affects others. We need herd immunity. Same reason other vaccines are mandated to attend public school. I agree though that with a new virus, the details change slightly as new data comes in. |

The vaccine is not 100% protective against infection, nor does it reduce transmission 100% (Both numbers appear to be in the 50%-80% range depending on the vaccine). This at minimum weakens the case for a mandate. As far as taking up hospital beds? You might as well make carelessly breaking your arm illegal. Consider that, in America at least, people are *paying* for their hospital beds, through insurance copays or out of pocket. They have as much a right to a hospital bed as the next person. |

Watch this old video from Milton Friedman's "free to choose" lectures, on this very debate. |

You didn't link an actual video. |

Oh, I thought I linked it.. here it is: |

This assumes that the vaccines are sterilizing. They are not: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2021/07/30/1022867219/cdc-study-provincetown-delta-vaccinated-breakthrough-mask-guidance The dropping efficacy and forever boosters makes it more of a sham. Moreover, for kids, there is no actual proof that it they are effective at reducing severe outcomes since the clinical trial didn't have any severe cases in either arm... they used immunobridging to infer the "level of protection" by correlating it to antibody levels. Even if they were effective at stopping spread or reducing severity, how is it at all ethical to force someone to take a medical procedure for someone else's benefit? If you are worried about COVID, you can get vaccinated and be protected. Yes, I understand some people can't get vaccinated due to health issues but I think that's a red herring. What percentage of the population is that? |

Fine, and then someone does develop cardiac problems in the long term, and then they/their family sue the doctor and the drug company and anyone else their lawyer thinks will stick over "you should have warned us!" "We did, and you accepted the risk?" "Well, you should have made sure this was perfectly safe!" "But you didn't want to wait for the trials and approval process, you wanted it *now*" "Well, you shouldn't have let us have it anyway, even if we wanted it and said we accepted the risk!" |

It's actually even worse than that. They are saying that *doctors* are too stupid to make the risk/reward decision for their patients. The drug will require a doctor's prescription. Doctors know the patients particular situation and have a lot of experience thinking in terms of risk/benefit trade-offs (unlike FDA stooges who use precautionary principle / are incentized just to minimize risk, and who have shown themselves to suck expected value thinking throughout the pandemic). |

> you would think someone could either do a cost-benefit analysis (the risk of letting one terrorist through is less than the risk of having all these people get executed after Kabul fell) or take the initiative to come up with some clever solution (airlift them to a military base in the US, let them wait there, and don’t let them out until the not-a-terrorist background check clears). For Vietnam, they called it Operation New Life and moved 50 thousand people to Guam in a month. I don't think I ever got a satisfactory answer as to why it wasn't possible to get started on something similar a decade ago. |

The US built the Arecibo Telescope in 01963, entered the Vietnam War in 01964, landed on the Moon in 01968, unilaterally "temporarily" reneged on redemptions of dollars in gold in 01971, made their last landing on the Moon in 01972, suspended combat activities in Vietnam in 01973, evacuated 130,000 refugees in Operation New Life in 01975, ended their manned spaceflight program in 02011 (although other countries still flew US astronauts, and in 02020 SpaceX resumed US manned spaceflight), allowed the Arecibo Telescope to collapse in 02020, and withdrew from Afghanistan in 02021. In short, the US in 02021 is not the same as the US in 01975. |

What’s with the leading 0s there? |

Maybe it's a Long Now thing? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Now_Foundation |

The US developed a COVID vaccine in 10 months in 2020. Maybe you should stop cherrypicking. |

Only one - moderna - was entirely a US developed vaccine as far as I can see. |

Some guys in Boston developed a covid vaccine in 4 days in 02020. Then it took them 10 months to be allowed to give it to people because of organizational dysfunction in the organization we're talking about: the US government. |

Yeh…it’s not like that had to test it to make sure it worked and was safe and scale up production. Nope they should have just instantly made up 600 million doses and hoped for the best. |

Good post. A historical parallel is the AZT trial for AIDS. In that case, after halting the trial early because of clear signs of treatment success, the FDA gave Compassionate Use exemptions to 4000+ AIDS patients. Let me quote from a summary post of mine (https://willyreads.substack.com/p/a-history-of-the-fda): "Phase 2 trials which had begun in February 1986 were halted early in September 1986 due to clear signs of treatment success, and AZT was officially submitted to the FDA for approval in December 1986. Eileen Cooper, a rising young star at the FDA, was in charge of reviewing it, and had been reviewing the AZT data for months before the official submission date. Even before the most militant AIDS activists had begun pressuring the FDA, she had been discussing with others on ways to speed and streamline the approval process. She took two important steps. First, in September 1986 she had released AZT for compassionate use to 4000+ AIDS patients, which likely saved many lives. Second, she sought the support of the FDA's Advisory Committee on Infective Drug Products in a January 1987 meeting, which would symbolically back up the FDA's decision to approve AZT on the basis of a single prematurely ended clinical trial. This would achieve two contradictory goals: the rapid release of a likely effective drug to suffering patients; and satisfy the consumer protection and public health voices that generally urged caution." So the FDA could and should have issued compassionate use exemptions for this drug, even going off historical precedent, while approval and paperwork checking was going on, as soon as the trial was halted for signs of treatment success. |

You answered my question below. Thanks! |

Ivermectin is not the best choice for that question. We should ask why is fluvoxamine not being given to every high risk patient? There you have efficacy data just as good as for Paxlovid, and a far better safety record. And there are around 20 other treatments where this question applies. The six weeks of extra deaths until Paxlovid approval is basically what's been going on since the pandemic started. Almost all pandemic deaths are due to the failure to deploy probably-effective-definitely-safe treatments. |

Author Agreed on fluvoxamine. |

If someone you knew got Covid, would you write them an off-label script for fluvoxamine? |

Author Yes. |

Having first made sure the person was not allergic to fluvoxamine, on medications that would interact adversely with it, or having an existing condition or co-morbidity that would be worsened, such as cardiac disease or a history of same in the family. There are several medications I can't take, because my doctor went "Let's put you on - oh, no, not with that condition of yours" or "let's try this new one, now there is the very remote chance of this side-effect but it's very rare", and after I took the first couple of doses I started getting the potentially very serious side-effect and had to discontinue sharpish, or else. For example, with fluvoxamine, there is the risk of QT prolongation which affects the heart rhythm, in sufficiently severe cases causing something lovely called torsade de pointes, "a specific type of abnormal heart rhythm that can lead to sudden cardiac death": https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torsades_de_pointes I know I'm susceptible to this, because I already have heart arrhythmia, and developed long QT interval after taking a common anti-histamine (fortunately for me, the cure there was "stop taking that and after a couple of days it will sort itself out"). So, no fluvoxamine for me, even if it works well for high-risk patients (and I'm the type who *is* a high-risk patient if I *do* get Covid). This is what drives me crazy about such demands for "Give everyone X!" because this is the kind of "read the small print" need that people calling for X don't take into account. |

I don't think there is the same level of evidence for fluvoxamine as for paxlovid. Paxlovid was developed specifically for SARS-CoV2 with (I think) a reasonably well understood mechanism of action. Their phase 2/3 study shows an effect on mortality as well as on the composite endpoint of hospitalisation or mortality. Fluvoxamine is repurposed; no clear mechanism of action; was trialled initially for a pretty random reason (some person thought why not https://online.flippingbook.com/view/329200553/9/). The main study shows an effect on a composite endpoint of "observation in A&E for 6 hours"/hospitalisation/death. Almost all the effect is on the least objective component of this composite endpoint, the observation for 6 hours in A&E. There is a good reason to think that participants, and possibly treating physicians were not completely blinded to allocations given the very large differences in adherence between the SSRI and placebo arms. So I would worry the effect is being driven mostly by behaviour. |

There was a trending effect for deaths. While not statistically significant, it was the same relative risk ratio as for hospitalizations (0.68), which argues against the hospitalization reduction being driven by unblinded subjective factors. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(21)00448-4/fulltext > "There were 17 deaths in the fluvoxamine group and 25 deaths in the placebo group in the primary intention-to-treat analysis (odds ratio [OR] 0·68, 95% CI: 0·36–1·27)" |

I'm not saying there is no evidence for benefit, all I'm saying is from a Bayesian perspective the probability that SSRIs actually are useful is less (lower a priori probability, higher likelihood that the results can be explained by chance+bias) |

SSRIs as a class show no effect on Covid outcomes (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.10.25.21265218v1.full.pdf). The beneficial effects are specific to fluvoxamine, and they aren't that great if you consider death to be an important outcome. |

Observational data from hospital records could be horribly confounded in all sorts of way and in either direction. "adjusted logistic regression model was run to account for age category, gender, and race" doesn't cut the mustard I'm afraid... |

Isn't the "per protocol" group pretty impressive? (1 death in the treatment, 12 in control). Is that a usual thing, to separately track a subset of patients who reported high adherence to the prescribed dosage? Naively it looks like a neat trick to me, if many patients aren't really taking the medication enough (because it's not administered in a controlled environment) then we're not really testing its effects and we should expect middling results, so let's focus on the patients who actually took the damn pills? I guess this biases for conscientiousness, but is that a cause for concern? I haven't really seen this "per protocol" thing before, genuinely curious what to think of it. |

It's true that per protocol is nearer to estimating the causal effect that one is interested in: ie the causal effect of taking the pills rather than the causal effect of being randomised to take the pills. The problem however with a per protocol analysis is that you are conditioning on a post randomisation event, thus possibly introducing confounding. You have to know the mechanisms behind why some patients are/are not adhering to treatment, and thus observe any confounders. Given the huge difference in the number of deaths between per protocol and intention to treat, I would suspect there is considerably confounding - not sure exactly how though |

I take your point, but also find comfort in that earlier small studies also had large effect sizes. The small randomized trial had 0 critical deterioration in treatment (n=80) vs 6 in control (n=72). The pseudo-randomized experiment at a racing track in California had 0 ICU/death patients in treatment (n=65) vs 2 in control (n=48), and what impressed me even more and made me strongly suspect there's a real effect here, 100% had no symptoms at day 14 in treatment vs 40% in control. Those studies were small, and one of them not truly randomized. But coupled with the latest large study's results I'm hopeful that there's actually a very strong effect on mortality that properly emerged in the per-protocol group, and is masked by lousy adherence in the general group. |

Isn't this the missing story here? Good to see lots of action on Paxlovid and related efforts, but where's the show on fluvoxamine? That stuff was already looking good a full year ago (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2773108). Why was its study not properly funded during the year? Don't governments have money to throw at a seriously promising treatment? Then last month the TOGETHER trial came out with clearly positive results, positive enough that it was stopped early for fricken *efficacy*.... and what do we hear? Crickets! Where are the FDA and the EMA? Where are their equivalents in Third World countries that would have the most to gain from it? I honestly don't understand. |

The Moderna vaccine was developed in March 02020, a few days after the genome was published. China was offering a covid vaccine to government officials and students who had to travel abroad in July 02020, a more traditional vaccine, I think. The Moderna vaccine was approved in the US in November 02020. Not just almost all pandemic deaths but almost the entire pandemic are due to the failure to deploy possibly-effective-probably-safe treatments. |

Yep, the Chinese vaccine is a bog-standard killed-virus vaccine. It turns out it's about as effective as the flu shot against Covid Classic: not that great, but a lot better than nothing. The big advantage of a killed-virus vaccine is that it's standard and easy to produce. MRNA vaccines use brand new machines which are super hard to make and use. Even if Moderna and Pfizer had been rubber-stamp-approved in March 2020, we wouldn't have been able to produce much of them for a long while. As it was, Pfizer was struggling to produce enough of its vaccine for the clinical trials. Maybe they would've gotten more if they'd actually been rubber-stamped in March and scaled up right then as fast as possible... but I wouldn't assume at all. |

Aren't the "brand new machines which are super hard to make and use" just thermocyclers? I guess I don't actually know how the mRNA vaccines are made. Aren't they just RNA? Whose quantity you can double with PCR once a minute? I'd think the problems you'd have with that would be more a question of purity, contamination, and mutation load, rather than production capacity. But what do I know? I've never so much as plated a bacterial culture. |

It's the microfluidic machines that stick the RNA inside lipid nanoparticles that's the bottleneck. This is needed to protect the mRNA from the RNAses we produce to make life harder for viruses. From what I've heard, they haven't managed to scale it up to industrial-scale equipment and are stuck running a bunch of bench-scale processes in parallel. |

"There you have efficacy data just as good as for Paxlovid". The TOGETHER study (fluvoxamine) did find a 99.8% chance of superiority over placebo for their primary endpoint of hospitalization, but the degree of superiority was no better than a factor of two (CI95% [0.52- 0.88]). For the secondary endpoint of death, the death rates were indistinguishable (2% vs 3%, p=0.24). In the Paxlovid study, the treatment arm had no deaths while the placebo arm had 10 deaths (~500 people per arm). If you care about dying, I don't think fluvoxamine is nearly as good as Paxlovid. Indeed, fluvoxamine appears to be worthless. |

"Despite two doses of Comirnaty, I was forced to take a regimen of Paxlovid". Seriously, the vaccine and the drug are great, but do they have to make it sound like we are living in a negative utopia? |

If effectiveness and safety were the reasons the FDA stopped the trial, then it makes no sense not to approve it. It would be interesting to know other examples of stopping a trial of drugs for the same positive reasons and when those drugs were approved. |

The same thing happened with Merck's drug, Molnupivir. The stoppage was mentioned in an October 1st press release: "At the recommendation of an independent Data Monitoring Committee and in consultation with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), recruitment into the study is being stopped early due to these positive results" The EUA legislation gives the FDA a lot of authority - they could EUA right now if they wanted. However, they won't EUA until the committee meeting, which they have scheduled for Nov 30th. https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-30-2021-antimicrobial-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting-announcement-11302021-11302021 So earliest EUA is Dec 1st, 9 weeks after the press release, and 7 weeks after Merck submitted their EUA application. Pfizer submitted their application Nov 16th. So the median Metaculus prediction of Jan 1st is in line with the Merck example, sadly (I say sadly because the death rate has been pretty steady at ~1,200 per day and case rates are going up again). |

Will rushing even save a single life? I'm skeptical. Unless the drug has an insanely short lifespan, there's a good chance there won't be enough to go around for months no matter what we do. |

By the way, I don't know _anything_ about biochemistry, but the new Merck RNA-garbling pill molnupiravir sounds a tiny bit ... terrifying. From StatNews: Will it affect a patient’s DNA? This is really a question only for Merck’s molnupiravir, since it works by sneaking subtly corrupted parts into the coronavirus’s RNA sequence. Once the virus has mutated too much, it can’t work — mission accomplished. But there’s a theoretical chance that molnupiravir could also influence normal human DNA when it replicates, too. If mutations happen during that process, it could spell real trouble. Merck did some tests during molnupiravir’s development to check this possibility out. In two different types of animal studies using higher and longer doses than are given to humans, Merck’s scientists didn’t see any increased risk of unwanted mutations. ... But UNC’s Swanstrom isn’t completely convinced that the tests Merck did were sensitive enough. In August, he and his colleagues published a paper in the Journal of Infectious Diseases showing that a key metabolite of molnupiravir could mutate DNA in animal cells. Given these results, Swanstrom said he would be particularly interested in seeing a long-term study of people who took molnupiravir to continue to monitor this potential effect over the next 10 or 20 years. "This thing is going to go into thousands of people. And are we just going to ignore the fact that there’s this potential risk?" he said. "The risk could be zero. It could be no worse than going to get a dental X-ray — or it could do something more. But unless we find out, you know, we’re going to learn this lesson the hard way, way later than we should." |

Merck's pill is said to be only 50% effective at keeping newly infected covid patients out of the hospital, compared to 85%-89% for Pfizer's new pill. So, if you can only take one, you'd want Pfizer's. But, if they operate wholly independently, it would be nice to have Merck's pill available to double the efficacy of Pfizer's pill alone. We need more tests to figure out if that is true. We also need studies of how these pills work on the vaccinated. I believe the initial efficacy studies are only of the unvaccinated in order to get a sufficient sample size fast enough. |

Much of the cost benefit analysis is predicated on Pfizer being able to unleash a flood of pills. If production takes time to ramp up and demand exceeds supply at any point during the initial post-approval period, then the cost (in lives) of the delay would be near zero. I don't know, and have not been able to find any information on, what Pfizer's production curve looks like. I'd love any sources on that folks could share. |

It would be near zero. In theory they could auction of the pills to the most efficient user. |

Probably the most efficient user is not in a position to participate in an auction because they are intubated and heavily sedated. |

It must be given in the first 5 days of symptoms so you've missed your window if intubated. That said, your point still stands. The person in a position to spend the most at auction is likely not the one who it will be most likely to help. |

Oh, I didn't realize that. Thank you. In that case an auction would probably be fine. |

If they've already got the factories churning under the assumption that approval will be granted, does it really matter in the long run? Like, those pills will be made tomorrow, they'll find patients to take them, they'll save lives. Whether they save lives in a week or in 2022 doesn't seem relevant from a policy perspective. And if drug availability is the bottleneck, it makes sense from an optics perspective to build up enough of a stockpile to not have stories about rationing and bare shelves as soon as approval is granted. |

I believe Scott's argument is essentially: it matters to people who die in the interim. |

Yeah, but Scott cares about (average predicted) number of lives saved. If 10 people get saved tomorrow, but then three months down the line 10 people die due to supply issues, how is that any better than waiting for approval and saving the latter 10? |

The 10 people saved tomorrow had no good alternative treatment options while the 10 people 3 months down the line will have other options besides this one because (following the lead set by this one) other new treatments are likely to have been approved. And we'll know more about how well this one works - like we might work out (based on the early use) that half-doses work well and thereby double the supply. |

One word I don't see mentioned anywhere is "manufacturing." It's one thing to make enough drug for a clinical trial, it's another to make millions of commercial doses reliably. FDA approval requires inspection of and confidence in these commercial-scale manufacturing processes. |

I was thinking this too. Although manufacturing shouldn’t preclude approval. |

To expand on this more: the clinical trials only show that *that one particular batch* was safe and efficacious (the FDA thinks this, since they agreed to terminate the trial early). Pfizer must then show that the commercial batches will be identical in every relevant way to the clinical trial batches, so that they will have the same safety and efficacy. What are the relevant ways? Pfizer must decide that, and justify their decisions to the FDA with supporting evidence. Scaling up chemical manufacturing is not trivial (a regular contender for Understatement of the Year). E.g. heating and stirring work differently in different sized reactors. Heat transfer in and out of your reactor works through surface area, but heat produced/consumed by the reaction depends on volume. If your stirrer design isn't right for the viscosity of the solution, you might get hotspots and so on. Ideally, the FDA expects you to understand the chemistry so thoroughly that you know everything that can possibly go wrong, and design your commercial process so that none of these things can possibly happen. The commercial batches will therefore be identical *by design* to the clinical trial batches, and you have to prove this with science. Of course in practice you don't have to have collected all the evidence before you can start selling batches, but you must have your plan in place with a solid scientific justification for every decision you made along the way. It also helps to have made a statistically valid number of commercial batches to show that your beautiful process works as designed (how many batches is that? you tell me, and justify your decision). Pfizer/Merck will have thrown everything at this problem alongside the clinical trials, as they can afford to do this, so their regulatory submissions will be pretty good. However they still might have to store the new batches for a few months to demonstrate that they have a comparable shelf-life to the old batches, and FDA might wait to see this data etc. Note that this really only applies to new chemical entities; people have been manufacturing fluvoxamine for years and its probably well understood by now. Not always true though; we saw a worst-case situation recently with the ranitidine withdrawal: a medicine that some reasonably healthy people take every day of their lives was shown to be contaminated with small amounts of a nasty carcinogen. If Pfizer happened to have some gaps in their understanding for the Paxlovid process, the FDA might go easy on them as dying of Covid now is worse than a slightly increased risk of cancer in the future, but it takes time to review all of these risks and make a justified decision. Expand full comment |

Yeah, unless the medication has an insanely short shelf life, it's likely that they'll be short on it regardless for months anyway as they ramp up production, and having bad batches of pills could kill use of the drug even if it does work. Same reason why we didn't just mass innoculate people with experimental vaccines last year - a lot wouldn't work, so it would undermine confidence in the ones that did. |

To also expand on this: There's a real-life example as well. The EMA (the European counterpart of the FDA) is still reviewing the Russian Sputnik vaccine, and says the current delays are due to their inspections of the manufacturing facilities. Some EU countries, e.g. Slovakia, did not wait for EMA approval, and bought Sputnik early on. Then they found that what they received wasn't really what they expected (a claim the Russians hotly disputed). https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/08/world/europe/slovakia-coronavirus-russia-vaccine-sputnik.html |

Thanks for this. I see the commentary from Scott and others about how "why doesn't the FDA just approve it already and save tons of lives", and all I can think is, "You should know better; it's a lot more complicated than that." Scott makes a lot of assumptions he doesn't even realize he's making when he assumes it's as easy as just churning out a bunch of this stuff in record time. I manage the clinical portfolio for a startup oncology-related pharma company, and I'm amazed when I see the speed at which some of these companies are pushing COIVD-related drugs. Every step in this process takes a lot more time than people realize, and there are a lot more steps than people realize. It's not just the regulations that makes this take time. It gives me a lot less confidence when I see Scott talking about something within my field of expertise and making wildly inaccurate assumptions, that when he's speaking about something outside my field of expertise he's not making the same wild assumptions. |

The people at the FDA have to read and analyze these applications which can run tens or even hundreds of thousands of pages. That takes time even if you have adequate resources, which the FDA does not. That’s how we avoid another thalidomide, which would be the worst possible outcome. They seem to have an all hands on deck approach here, but it does take time, and it is necessary to dot all the I’s and cross all the T’s. Perhaps I am being too solicitous, but that’s my take on this situation. |

We are accepting a virtually guaranteed cost of tens of thousands of lives in order to hedge against a very remote risk of a repeat of an event that cost thousands of lives (which you describe as the worst possible outcome). That isn't being solicitous. That is being irresponsible. |

Perhaps, but such an outcome would destroy the credibility of an agency that we really need, as if they haven’t done enough damage themselves recently. |

Saving lives is far more important than the FDA's reputation, not that their reputation is still salvagable. |

Unfortunately FDA's reputation is the metric people use when deciding whether to trust any new FDA-approved vaccine/drug. Every lost point of FDA's reputation could potentially mean another million of lives lost in the next pandemic. |

This is such a bizarre claim to make with no evidence. It’s pretty clear from this pandemic, that people will distrust drugs for reasons that are impossible to predict or control. So why are you advocating doing the wrong thing in order to hedge reputation? It reputation strategy doesn’t even make sense either. You are trading off the guaranteed and very severe reputation damage if withholding life saving medicine from dying people. With the unlikely and less severe reputation damage if doing the wrong thing and getting unlucky. It’s poor logic all around. |

The FDA does no research into what affects its reputation and how its reputation affects lives saved. They are, as Josh Barro writes, amateurs when it comes to psychology. https://twitter.com/jbarro/status/1463149716775047172 |

Institutional reputation is more valuable. We're seeing the costs of institutional reputation lost every day here and it's very, very real. I get that you think they're just dumb people, but we're talking about net lives lost and the only reason we're talking about the cost/benefit of rushing this drug to market is because of institutional reputation lost that's stopping 50% of the country from taking the proper preventative measure. |

Dr. Marty Mackary says this : "As a Johns Hopkins scientist who has conducted more than 100 clinical studies and reviewed thousands more from the scientific community at large, I can assure you that the agency’s review can be done within 24 to 48 hours without cutting any corners." https://thedispatch.com/p/fda-career-staff-are-delaying-the also keep in mind we are not talking about full approval here and the requirements for what needs to be in an EUA application is all stuff the FDA invented during the pandemic (the EUA legislation, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/21/360bbb-3) only requires that "known and potential benefits of the product... outweigh the known and potential risks of the product" |

You know what a 3-legged race is, right? Two people run as a unit, with the left leg of the person on the right tied to the right leg of the person on the left. The unit does not run nearly as fast or as well as a single two-legged runner. Well, organizations like the FDA are like a 5000-legged race. All these people are tied together in various ways so that the whole mass takes the shape of a 4-legged beast, eachleg made out of 100's of people tied together leg-to-leg, head-to-toe, or human-centipede style. Then the big fucker tries to walk a few blocks. You will not be surprised to hear that it does not walk fast or well. |

Pfizer issued a press release on 11/9/2020 of the unblinded results of their vaccine. (As StatNews made clear that day, Pfizer had curiously shut down processing of their results from late October until the day after the election, likely delaying release of the positive news until after election day. Perhaps not coincidentally, leading Democrats like Biden and Harris and Democratic-affiliated scientists had been spreading Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt all fall about the "Trump Vaccine.") The FDA's issuance of an EUA came 32 days after the press release on 12/11/20. The UK started giving Pfizer jabs on 12/8/20 and the US started giving Pfizer shots on 12/14/20. The initial rollout over Christmas was pretty lackadaisical in the US outside of a few states like West Virginia and the Dakotas and didn't really get into gear nationwide until later January. |

It seems to me the same people who complain that they are being idiots for not doing something are the same folks who will complain when they do something and it blows up in their face. Tons of 20/20 hindsight, etc. |

Author I hereby commit to not complain if the FDA approves a drug too quickly and it blows up and causes problems, unless they were really stupid about it and any moron should have been able to figure out it was bad in the same amount of time the FDA took. |

Anyone can look like a moron in 20/20 hindsight. |

Agree. But some people who look like morons in hindsight could have gotten better marks from the judgment of history if they had been smarter or more honest or just tried harder. Others assessed the facts they had well and acted with great energy and smarts, but can look dumb in retrospect if you don't bear in mind that there was crucial info they just did not have access to. |

Why does it seem to you that way? Do you have any evidence for it? In my experience an awful lot of FDA critics are people like me who just want the FDA to get the hell out of the way or be entirely abolished. Whether people use a drug should be up to those people, their doctors and their pharmacists. If we make FDA approval voluntary, let anyone sell drugs with a "not approved yet" sticker then by definition it's not the FDA's fault when drugs people use don't work. Nobody is asking the FDA to *guarantee safety* of these drugs, we're simply asking them to let the drugs be used REGARDLESS of whether the FDA is satisfied with their safety. |

Bad actors will ruthlessly exploit and maim America’s legions of morons. You don’t care about them but most people do. |

"Nobody is asking the FDA to *guarantee safety* of these drugs, we're simply asking them to let the drugs be used REGARDLESS of whether the FDA is satisfied with their safety." Which is how things used to be before approval bodies were set up, and people were being marketed a range of substances from the useless to the actively deadly. If you're happy to go back to "you have a condition, this treatment might not work or it might kill you or maybe, very seldom, it can help" then good luck to you. I would rather know "if you take this drug in combination with that medication you are already on, it's going to make your liver explode, so don't do that!" |

> I came away from the pushback convinced that nobody would ever believe the FDA was dragging its feet until I could make them read about it in flagro delicti - write a post saying the FDA is dragging its feet now, on this thing that you and I currently realize is obviously good. Should be "in flagrante delicto" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_flagrante_delicto). "In flagro delicti" means "in the whip of the crime". |

Out of curiosity, does "stop the trial" mean "stop collecting data and give the drug to everyone in the control group" or does it mean "stop collecting data and stop giving the drug to anyone". if it means the latter, then I fail to see how "it would be unethical to continue not giving to to the control group" makes sense, given that the potential control isn't getting it either way. |

Author I assume it means the first one, on the same reasoning as you. |

I'm actually not so sure. It is true that sometimes they give the drug to people in the control group for ethical reasons, but in the case of the vaccine trials it took several months before the participants were unblinded, and only after some protests were raised (I heard a participant on NPR for instance demanding to be unblinded and allowed to get the vaccine in spring this year). |

Haven't read the pre-registration, but given the nature of the drug, I assume that the participants were recruited as they were contracting Covid. So as soon as the trial had been stopped, there were no new participants in either the control or the treatment group and hence no one to give or not give the drug to. (I'm also assuming that the people previously entered into the control group are out of the treatment window at that point anyway). Had the trial continued to recruit participants, putting each new participant into the control group would mean performing an action that would knowingly increase that person's risk of death or severe illness (as opposed to putting them into the treatment group). But if you're not recruiting any new participants, you're not knowingly increasing any particular person's risk of death. The vast majority of people that would contact Covid in the interim would likely not have been participants in the trial anyway, so none of them can say that their risk was significantly increased by stopping the trial. |

They already had contracted Covid: "About the Phase 2/3 EPIC-HR Study Interim Analysis The primary analysis of the interim data set evaluated data from 1219 adults who were enrolled by September 29, 2021. At the time of the decision to stop recruiting patients, enrollment was at 70% of the 3,000 planned patients from clinical trial sites across North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, with 45% of patients located in the United States. Enrolled individuals had a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection within a five-day period with mild to moderate symptoms and were required to have at least one characteristic or underlying medical condition associated with an increased risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19. Each patient was randomized (1:1) to receive PAXLOVID™ or placebo orally every 12 hours for five days." |

It completely has to do with equipoise and informed consent. Equipoise means that, with the available evidence, you're not certain which treatment is better. Once you've done a pre-specified interim analysis that shows that one treatment arm is better (like happened with paxlovid), you no longer have equipoise. The second issue is informed consent. Before enrolling in a trial, a patient has to be told the risks and benefits of entering the trial. At this point, to enroll a patient in a paxlovid v. control trial honestly, a doctor would have to say something along the lines of, "You'll be randomized to either a good treatment or a bad treatment." To be clear, I am also frustrated by the delay between the trial being stopped for efficacy and the FDA approving a medicine I wish I could prescribe. I'm not sure what the reasons for delay are, and I would love to hear the perspective of an insider because I would really just be speculating as to why it takes so long. But I think a lot of the discourse I am seeing in this thread are looking at the pros and cons of early approval are narrowly focussed on COVID lives saved or lost rather than the integrity of a system of investigation and regulation that has allowed for BILLIONS of life years of meaningful life extension. It seems to me with the limited information that I have that the FDA could speed things up without significantly increasing the chances of a catastrophic miss where many people receive an unsafe medicine. I'm really curious what insiders at the FDA would candidly say about unreasonable delays. However, the downside to a catastrophic miss (no matter how unavoidable) is that it further undermines the trust in this system (which is already pretty low). The FDA's reputation matters ENORMOUSLY to many questions outside of COVID and far into the future. How much needless death and suffering have we seen because of poor vaccine uptake? And how much of that poor uptake was due to a lack of trust in regulatory institutions? |

I'm uneasy with the elimination of a control groups by ending a trial early and giving the drug to the control group. They did this with the vaccine, too. Okay, it's hard to say no to the obvious humanitarian argument. Still, at the point when the control group is eliminated, all we've learned is that the drug seems safe and effective (for some p-value) in the short-term; we don't know anything about the long-term. |

I think you underestimate the power of very, very large observational "post-market" follow-up studies which the FDA often requires. We know that serious side-effects from vaccines are almost always rare (< 1 / 100,000) so you need very large sample sizes to detect them in any case. I'm not aware of any previous vaccine having long term side effects, nor of any scientific reason for believing that would be possible. Do you know of any examples? |

> We know that serious side-effects from *modern vaccines* are almost always rare These are new mRNA vaccines. What quality of them makes you feel the long-term effects of them are comparable to the modern vaccines in this historical way? |

Because mRNA goes away after a short period of time. Vaccine injury will pretty much always appear very rapidly simply because the vaccine doesn't stick around at all, so there's nothing there to cause further injury. |

mRNA is unstable and disappears very quickly. mRNA vaccine tech has been in development for decades.. in 2013 there was a mRNA vaccine for rabies that was tested in humans. There's also been mRNA vaccines for cytomegalovirus and Zika tested in humans. it's also conceptually not much different than viral vector vaccines (using DNA) which have been developed for Ebola previously. there's no biologically plausible mechanism which could lead to long term effects and it seems to me we understand this area of biology pretty darn well at this point |

> I'm not aware of any previous vaccine having long term side effects https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223724/ "It is well established, for example, that the oral polio vaccine can on rare occasion cause paralytic polio, that some influenza vaccines have been associated with a risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome" |

Many vaccines can cause Guillain-Barré syndrome in about 1-in-a-million. My understanding is that Guillain-Barré is rapid-onset, so it shows up quickly once you have a lot of people taking the vaccine. The polio vaccine is a really interesting case because some polio vaccines are a weakened but live virus. That virus can mutate over time and spread from person to person. So in that case I see the potential for longer-term risks. But that's a special case and the mechanisms there don't apply to CV-19 vaccines. https://www.npr.org/2019/11/16/780068006/how-the-oral-polio-vaccine-can-cause-polio There is a longer-term risk for Molnupiravir to cause evolution of a more dangerous virus that might interest you. I've read about it and it seems a very low risk (especially considering CV-19 seems to be at an evolutionary dead end) but it is there. See: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/molnupiravir-mutations |

The other side of this concern is that people are assuming the positive side of the results are statistically valid. Oncology trials are often stopped early for ethical reasons, similar to the rationale in this study. The result is that trials stopped early are much more likely to overstate the treatment effect. This is selection bias at work. I'm sure there are also trials closed down early due to lack of efficacy, but those are usually closed down because even if the remainder of the patients responded to treatment it wouldn't have been enough to generate a sufficiently positive result to continue. I'm not saying there's not efficacy for this drug. I'm saying it's unwise to assume it's as high as 90% because it was stopped early. |

^ that's a good point. My guess/hope is data safety monitoring boards that monitor trial results in real-time try to correct for in their statistical analysis but how good a job they do, I don't know. I want to mention again that observational studies, like case-control studies, can provide more info on the efficacy at a later date. |

"Like everyone else, I hate the fact that pharmaceutical companies are the only people with enough resources to run high-quality studies, and that this controls what drugs we end up using." For COVID the single most influential clinical trial in terms of drugs we are (and are not) using is RECOVERY - not a pharma led trial |

One thing that I agree with the ivermectin conspiracy theorists on is it's really odd and bad that the NIH never funded a large scale trial on ivermectin early on. |

It seems entirely reasonable to wonder why it ever had to be 'amateur hour' with ivermectin testing. Well, 'wonder' is not stating it genuinely. It seems entirely reasonable to observe that there was an obvious motive not to trial ivermectin with the same zeal as Paxlovid. |

Why didn't the pharmacy companies do these types of studies for Ivermectin? |

Ivermectin is already approved. And probably out of its patent protection time. |

Yes but I mean they all vilified Ivermectin for its ineffectiveness, without ever doing large-scale studies like they did for these "newer" drugs. And of course all you would have left to study it are smaller studies because the engine that drives our studies here appears to be those same pharmacy companies. Is that not a catch-22? |

Did the pharma companies do the reviling? I thought they were rather quiet about it. |

Merck came out with a public opinion piece on their website against it. |

Author They did eventually do large-scale trials: RECOVERY and TOGETHER. They didn't work. The reason Paxlovid started with a large trial and ivermectin started with small ones is that Paxlovid is a new medication that requires pharma support to get through the FDA process, and ivermectin was an old one that was getting boosted to attention by the efforts of random individual doctors. Once the random individuals boosted it to the system's attention, people ran the big trials and they failed. |

Ron DeSantis and the government of the State of Florida could have directed the hospitals and medical schools to conduct a study. They didn't. |

While some of those studies were truly useless, small studies and those with weaker methodological rigor are very useful in helping determine where to follow up and focus large rigorous trials. In the case of Ivermectin, the follow-up trials did not prove out the large effects that were hoped for. Paxlovid didn't have small weak studies because it was purpose built to fight Covid. |

> the follow-up trials did not prove out the large effects that were hoped for. When I hear about this, I want to investigate the design of the studies and any conflict of interests. I desire to learn how to analyze study design more and whether something was off. Any suggestions on ways for me to apply this methodology to studies like the ivermectin large-scale follow up studies? |

I don't know what you mean by "apply this methodology," but I thought Scott did a really good job with his writeup a few posts back. |

I mean to say I am looking for ways to increase my ability to read studies and also analyze for design flaws and issues with the studies, and wondering what the best way to approach that might be. Maybe a book or other knowledge base. |

This is a great question and I don't have a fantastic answer for you. Going from zero to synthesizing a heterogeneous set of studies in some scientific domain is a long road. I have a PhD in statistics, have worked in infectious diseases for over a decade and been a statistician on several clinical trials. Yet there are still areas that I don't feel comfortable with my own ability to critique the literature (e.g. All the stuff around furin cleavage sites etc.). Looking at my bookshelf, the closest thing to helpful would probably be "Fundimentals of Clinical Trials." Very few equations, and I don't think the material requires much in the way of prerequisites. |

You could check out the Studying Studies series by Dr. Peter Attia. I haven't read all of it but he seems very knowledgeable on the topic. |

> I know I’m not going to convince many ivermectin supporters. So consider this: ivermectin is FDA approved. It’s approved against parasitic worms, but that’s fine: once a drug is approved for anything, any doctor can (more or less) use it for whatever they want. Doctors can absolutely prescribe ivermectin right now if they want, and many of them (like Pierre Kory) have. The ones who don’t prescribe it are avoiding it because they think it doesn’t work, not because the FDA is trying to prevent them. False. You seem to be a bit removed from the situations hundreds if not thousands of patients have faced. Doctors even. Doctors getting placed on leave, fired, discouraged from prescribing Ivermectin. Even Pharmacists are banding together on /r/pharmacy saying they won't fill the prescriptions. Heck, Dr. Paul Mark, Front line critical care doctor, suing Sentara hospital in Virginia because Board of Directors wouldn't let him prescribe it. |

>The medical regulatory system has made prescribing ivermectin legal and easy. The medical regulatory system has failed us. It has started to play doctor, and prevented doctors from practicing medicine and prescribing drugs like Ivermectin that their education trained them for. |

"The medical regulatory system has failed us. It has started to play doctor". That's actually pretty funny. |

Suppose ivermectin does feck-all as regards Covid. Your doctor shrugs and prescribes it anyway when you demand it, because it won't kill you. Best case: it does nothing. You have wasted time and money taking a pill that won't do anything for you. You might as well have been taking sugar tablets. Worst case: it does nothing. You are convinced you are now shielded from Covid, so you don't get vaccinated, you don't take precautions, and you contract Covid. And maybe you are a high-risk patient, so now it turns severe and you have to be hospitalised. |

I came to the comments section specifically to make this same point essentially (but perhaps a bit more cordially). To Scott, I definitely recommend doing a bit of research on the current ivermectin off-label prescription situation. While in *some* jurisdictions and hospitals you can prescribe it and patients can receive it, there are *many* situations around the US where doctors are not allowed to prescribe it and when it is prescribed it is not uncommon for people to find it very difficult to actually acquire because pharmacists are refusing to fill. I know that what you have described here is how the US medical system is *supposed* to work. Off-label prescriptions are a core part of the US's medical establishment. However, in the case of ivermectin specifically the system has become somewhat dysfunctional in some areas (not all). If off-label prescriptions weren't being bureaucratically/administratively blocked then I would generally be OK with the current situation. If some doctors think it works and they prescribe it and people can get it and others don't think it works that is OK. In the long run the doctors with a track record of treatment success will come out the winners, and there will be a survivor bias in the future towards patients who utilize those doctors. The problem is that when you make a drug hard to acquire, the marketplace of medicines no longer functions properly. It is like a prediction market where there is some external downward pressure placed on anyone who bets on one of the outcomes (e.g., higher fees for people betting on one side). This can skew the final results and potentially cause an incorrect prediction. Market economics only function when they are free from constraints, which is not the case with ivermectic (regardless of whether it works). |

Hospital administration is not the FDA (and not even a part of the medical regulatory system). I know it's a small consolation to people trying and failing to get/prescribe Ivermectin, but FDA is not the one to blame here. |

While I agree that the FDA isn't *directly* to blame for the ivermectin restrictions, I don't think they are helping the situation with things like their infamous "you are not a horse" tweet. That being said, the statement made by Scott is not entirely true: > Doctors can absolutely prescribe ivermectin right now if they want, and many of them (like Pierre Kory) have. The ones who don’t prescribe it are avoiding it because they think it doesn’t work, not because the FDA is trying to prevent them. While the last bit is true (the FDA isn't the agency blocking people from off-label prescriptions), the rest of the statement is not true for many doctors and patients in the nation. There are doctors who *cannot* prescribe ivermectin if they think it is the best treatment for their patient and there are doctors who avoid prescribing it not because they think it is ineffective but because they fear for their employment/career prospects. There are definitely some doctors who think ivermectin doesn't work, and I fully support them *not* prescribing it to patients. What I don't support is patients being unable to switch doctors to one who will prescribe/administer it, or patients who do get a prescription being denied the ability to fill that prescription by pharmacists (who shouldn't be deciding which medications are appropriate for a given patient). |

Yeah, I guess the proper way to say it would be "The ones who don’t prescribe it are avoiding it because they OR THEIR BOSSES think it doesn’t work" |

I think that is a plausible scenario. It is also possible that there are perverse incentives that cause people to not prescribe it even if it might work. I think such behavior is much less likely to be seen in doctors and more likely to be seen in administrators. Politics are incredibly ugly/dirty, and I *assume* that we can agree that at this juncture the line between medicine and politics (particularly around COVID-19) is thoroughly blurred. One can *imagine* some administrators making decisions based primarily on politics, and those decisions then getting pushed down onto the doctors/pharmacists. |

Curious why people don’t feel the same sense of urgency about lives lost, say to lack of medical insurance, in this country? |

Well for starters, because lack of medical insurance won't kill me or anyone I care about, whereas covid might. |

Because the FDA cannot issue an emergency use authorization for a single-payer health care system. (Although I'm sure some people in the Biden administration are exploring that.) |

Author Causing harm seems worse than failing to prevent harm. If the government banned me from feeding my child, and sent cops to my house to make sure I didn't sneak him any food, this seems worse than the fact that there are children starving because they can't afford food - or at least it's easier to complain about. |

"Causing harm seems worse than failing to prevent harm". I'm sure the FDA thinks that way, too. |

Given the topic is them causing harm in an effort to not fail to prevent harm, what makes you say that? |

Everyone seems to be talking as if this is a new miracle cure - take it and you won't contract Covid, or if you have it, it will clear it right up. I'm not seeing that, and the EMA is also not approving paxlovid on the bare trial results alone, although they want it as fast as possible: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-starts-review-paxlovid-treating-patients-covid-19 "Paxlovid is an oral antiviral medicine that reduces the ability of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) to multiply in the body. The active substance PF-07321332 blocks the activity of an enzyme needed by the virus to multiply. Paxlovid also contains a low dose of ritonavir (a protease inhibitor), which slows the breakdown of PF-07321332, enabling it to remain longer in the body at levels that affect the virus. The medicine is expected to reduce the need for hospitalisation in patients with COVID-19." And that's the summation there: "the medicine is expected to reduce the need for hospitalisation". Not "cure you completely". Not "prevent you ever getting it". Not even "nobody will need to go to hospital". REDUCE the need. Let's all calm down a little, okay? |

Because we know how to fix "lives lost for lack of Paxlovid" without causing any risk to anyone who doesn't choose to take the drug. We don't know how to fix "lives lost for lack of medical insurance" without tearing apart our current healthcare system and risking everyone who might have to interact with it ever. |

Because we're aware of things like the Oregon Experiment? Having medical insurance makes people use more health care but doesn't make people notably healthier. If you think lack of medical insurance causes lives lost that is a claim that needs some support, it can't simply be assumed. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa1212321 |

If by healthier, you mean specifically "prevalence or diagnosis of hypertension or high cholesterol levels [or] ... prevalence of measured glycated hemoglobin levels of 6.5% or higher", then sure. On the other hand, if you look at depression levels, or catastrophic expenditures, then it helped with those. Of course, the study specifically looked at able-bodied adults under 65, so it's unclear to what degree the results generalize. |

Depression levels & catastrophic expenditures are a far cry from "lives lost". |

Uh, not always that far, unfortunately. |

Rates of depression tripled under COVID: https://www.brown.edu/news/2021-10-05/pandemic-depression But suicide rates went down: https://www.worksinprogress.co/issue/why-didnt-suicides-rise-during-covid/ |

Ok, but the context here was regarding having and using health insurance, not COVID and lockdowns. |