Rome’s Colosseum Was Once a Wild, Tangled Garden

Rare plants and Romantic poetry tell a forgotten history of the ancient ruin.

When the botanist Richard Deakin examined Rome’s Colosseum in the 1850s, he found 420 species of plant growing among the ruins. There were plants common in Italy: cypresses and hollies, capers, knapweed and thistle, plants "of the leguminous pea tribe," and 56 varieties of grass. But some of the rarer flowers growing there were a botanical mystery. They were found nowhere else in Europe.

To explain this, botanists came up with a seemingly unlikely explanation: These rare flowers had been brought as seeds on the fur and in the stomachs of animals like lions and giraffes. Romans shipped these creatures from Africa to perform and fight in the arena. Deakin takes care to mention in Flora of the Colosseum of Rome that the "noble and graceful animals from the wilds of Africa ... let loose in their wild and famished fury, to tear each other to pieces"—along with "numberless human beings." As the animals fought and died in the arena, they left their botanical passengers behind to flourish and one day overtake the building itself.

This incredible piece of conjecture is hard to prove, but it shows just how much of the story of a ruined place can be found growing in the cracks between broken stones. Deakin, an Englishman from Royal Tunbridge Wells, opens his volume by calling the plants growing in the Colosseum "a link in the memory" that "flourish in triumph upon the ruins." He lists their ancient medicinal properties, notes the species of fern that must have grown around the Fountain of Egeria, and pauses at one point over a particular species of grass that might have ringed the banks of Nero’s fish pond. The grasses that grow "in matted tufts," he writes, "seem to be perennial weepers ... mourning over the vast destruction that reigns around them."

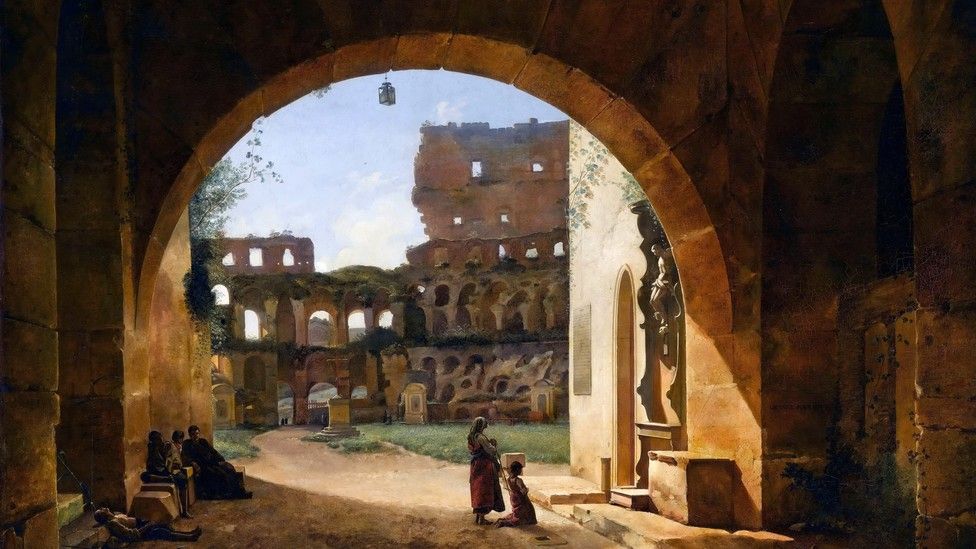

Today, the Colosseum stands bald and bare. But for centuries, it was a wild and overgrown place, and its lost history as a primeval garden ruin has left traces in the art and poetry of countless generations that walked among its stands.

* * *

By the time the artists and painters of the Romantic Age began to turn their interest to the ruins of ancient Rome, the Colosseum had suffered greatly. Since the days of Rome’s flourishing, the great arena had been a cemetery, a quarry of quicklime, a rich family’s fortress, and a bullring. In the 16th century, it was even explored as a site for a wool factory staffed by former sex workers. It had been damaged by fire and struck by earthquakes five times, including one in 1349 that caused the entire outer south side to collapse.

Due to the belief that Christian martyrs had once been fed to the lions in the arena, the Colosseum was also a popular pilgrimage spot. Despite little evidence that Christians were ever actually killed in the arena, in 1749, Pope Benedict XIV endorsed the view that the Colosseum was a sacred site, outlawing the use of its stones in other buildings. By that point, the arena was a crumbling ruin. But it had become the home for a great variety of sumptuous greenery.

Plant life was so abundant in the ruined arena that at certain times in history, peasants had to pay for permission to collect the hay and herbs that grew there. It had become its own miniature landscape, and formed a perfect microclimate for biodiversity: dry and warm on its south side, cool and damp in the north. Pink dianthus grew down in the lower galleries, while white anemones dotted the stands during spring.

When the Italian scholar Poggio Bracciolini visited in 1430, he mourned over the site of the ruins. "This spectacle of the world, how it is fallen!" he exclaimed. "How changed! How defaced! The path of victory is obliterated by vines." But others saw an alluring beauty in the arena’s greenery. Charles Dickens, in his 1846 Pictures From Italy, talks about his impressions on first seeing the Colosseum, and mentions the plant life there in particular detail, as a natural force reclaiming the site of past glory:

To see it crumbling there, an inch a year; its walls and arches overgrown with green; its corridors open to the day; the long grass growing in its porches; young trees of yesterday, springing up on its ragged parapets, and bearing fruit: chance produce of the seeds dropped there by the birds who build their nests within its chink and crannies; to see its Pit of Fight filled up with earth ... is the most impressive, the most stately, the most solemn, grand, majestic, mournful sight conceivable.

By the 19th century, countless painters and artists had visited the Colosseum and painted vistas of the arena’s overgrown stands and crumbling stones. The Scottish painter William Leighton Leitch (1804–1883) painted the Colosseum as an imposing empty space, a monumental hanging garden reminiscent of Babylon. Joseph Mallord William Turner’s "The Colosseum, Rome, by Moonlight" (1819) shows an almost tropical garden growing in the arena’s shadows:

For Ippolito Caffi, meanwhile, the ruins became an almost nightmarish vision, a primeval jungle ruin where strange lights dance between the stones wreathed in matted vines. The paintings that perhaps most effectively portray the strange, paradoxical atmosphere of the Colosseum in those days are those of Danish painter Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783–1853), who captures the abundant greenery growing in the Colosseum’s stands as well as its lost history as a place of Christian worship, but does so with a faultlessly modern eye, never giving in to the Romantic excesses of some of his forebears. His paintings are by turns infused with a solemn quiet, and full of the life of common people.

Paintings like these inspired writers as well. In 1833, the then-unknown Edgar Allan Poe was able to publish a poem called "The Coliseum," though he had never set foot in Italy. The poem mentions the flora of the arena particularly, with the lines, "Here, where the dames of Rome their yellow hair / Wav’d to the wind, now wave the reed and thistle."

Earlier, in 1818, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote lyrically of the way that the arena had itself become a natural entity, a landscape rather than a building.

It has been changed by time into the image of an amphitheater of rocky hills overgrown by the wild olive, the myrtle, and the fig tree, and threaded by little paths which wind among its ruined stairs and immeasurable galleries: The copsewood overshadows you as you wander through its labyrinths, and the wild weeds of this climate of flowers bloom under your feet.

Lord Byron, in the fourth canto of his "Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage," also speaks of the "The garland-forest, which the gray walls wear, / Like laurels on the bald first Caesar’s head." For him, the gaps and blanknesses in the ruins form portals to another time, bringing back the dead and unsettling the ruin-gazer.

But the abundant green life of the Colosseum was soon to come to an end. In 1870, Rome was captured by Italian nationalist forces, the final defeat of the Papal States in the war to unify the Italian peninsula. The Pope became an exile in his own palace, surrounded by armed soldiers who stopped him from appearing in public. A year later, Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, a new nation that was to be modern, democratic, and secular. As revenge for the Pope’s intransigence, Catholic convents, churches, and hospitals were seized for barracks. The Colosseum, too, was swept up in this upheaval.

As nation-states were being born around Europe and the rest of the world in the late 19th century, many of these new states reached back into their pasts to find a foundation on which to build their identities. The new Italian nation found this opportunity in the lost splendor of the Colosseum. The Italian government soon handed control of the arena over to archaeologists, who set about removing religious icons installed by the Christians and clearing it of its invasive greenery.

The work of these early archaeologists continued into the 20th century, and the Colosseum was finally totally denuded and its arena excavated under Mussolini’s fascist government, who sought even further to associate the modern Italian state with the monuments of ancient Rome.

* * *

Despite this loss, the Colosseum is today still a haven for plants. A study carried out between 1990 and 2000 found 243 distinct species still growing there, although this number is scarcely half what Deakin observed in the 19th century.

Plants growing today in the Colosseum include very rare species like Asphodelus fistulosus and Sedum dasyphyllum, which scientists believe can only survive when sheltered by the arena, a sanctuary from the urban environment outside. Due to increased pollution and the rising temperature of the city, the flora inside the ruined walls are beginning to change: Plants suited to a warmer and more arid climate are beginning to proliferate at the expense of those more used to cool and damp.

From the wild and magical ruins of the Romantic Age to the haunted and skeletal ruins of Dresden and Stalingrad, the place ruins hold in the collective imagination has always been as unstable as the crumbling structures themselves. No one sees the same ruin. Certain parts of a crumbling building, the ancient stones and arches, for instance, are deemed "proper." Other parts, like the plant life and the later historical stages of the ruin, are deemed "improper" and are removed.

Increasing attention is being paid to these intangible elements of a building’s story, and archaeologists and conservationists alike are having lively debates about how the atmosphere of these sites—the inspiration for so many artists—can be preserved. Deakin believed that the wild spirit of a place can "teach us hopeful and soothing lessons, amid the sadness of a bygone age." Today if you walk around the Colosseum, you might even see the occasional rebellious caper plant growing there, in defiance of security.