Nextdoor: Old Model, New Networks

diff.substack.com · by Byrne HobartIn this issue:

Nextdoor: Old Model, New Networks

Ads and Unit Costs

Which Features Work

Buy Now, Pay Later

Tech Nationalism

Returns

Part of the story of any new industry is figuring out the KPIs. New companies often know something is working, but they don't know quite what to manage for. This has happened at a high level, like when Du Pont figured out how to think about the drivers of return on investment, a very important detail for a capital-intensive business that relies on inputs with volatile pricing. And it's happened for specific industries: both Microsoft and Netflix took their time cracking down on piracy, since it benefited their network effect more than it hurt their pricing power.

Choosing these metrics doesn't just give managers a way to see whether or not they're doing a good job this quarter; it's a way to talk about what the business is for. If the long-term goal is to maximize the metrics, it says something specific about the end state the business is aiming for. MySpace and Friendster were implicitly targeting a world where everyone has a profile, but Facebook wanted a world where everyone's life was mediated through Facebook.

And yet the world does still have social networks. One of them, Nextdoor, is going public through a SPAC at a $4.3bn valuation. Nextdoor is a neighborhood-level social network. It has the usual features—profiles, posts, photos, ads—but they're all tied to specific locations. One way to look at Nextdoor is that it has turned into a way to replicate Facebook's early growth hacks, but to keep using the most durable ones for longer.

Facebook enforced a real name policy through email addresses, bootstrapping off the fact that colleges have to authenticate students. Nextdoor confirms user locations by mailing them a postcard.

Facebook grew by launching on one campus at a time; Nextdoor grows one neighborhood at a time, and uses neighborhood-level penetration as a key metric. One of the ways Facebook pitched itself to investors in the very early days was to talk about how quickly it could get more than half of students at a school to start regularly using their accounts; Nextdoor's investor deck talks about how much growth they'll have (4.5x!) if all the neighborhoods they operate in hit the same activity level as their most mature locations. If Facebook's goal was that you'd recognize classmates online, Nextdoor's goal is that you'll recognize neighbors online.

Facebook was able to maintain high usage by being the default place to organize on-campus events; Nextdoor also works as a way to promote events to people who live within walking distance.

At a more granular level, both companies got very good at linking the real-world social network to their digital one: Nextdoor cites contact syncing as a way to increase growth; Steven Levy's Facebook book says that one reason FB raised money from Microsoft was so that Hotmail would stop marking so many Facebook invitations as spam.

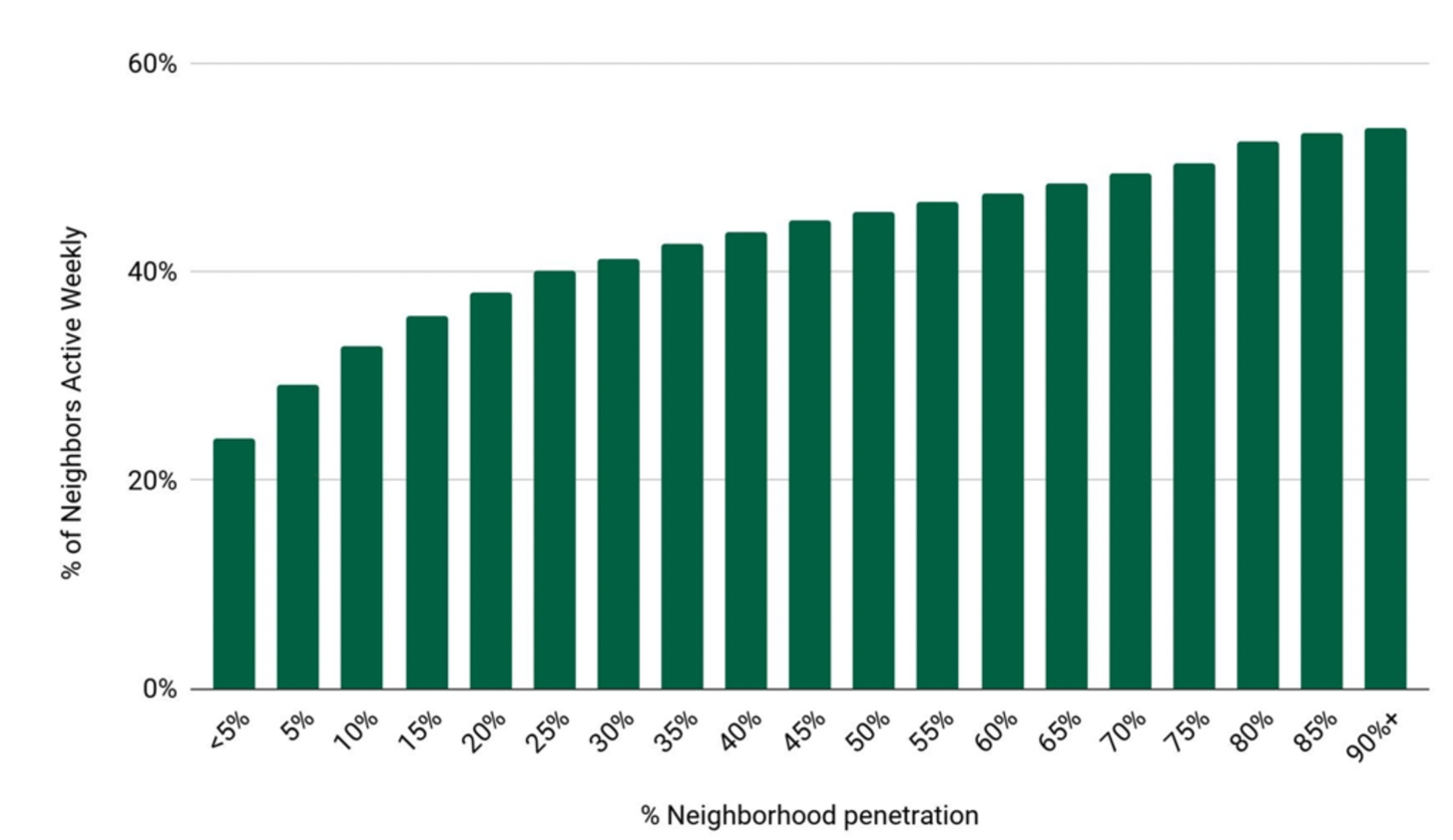

On both apps, users beget usage: Nextdoor has a very compelling chart showing that the higher its penetration is in a neighborhood, the more frequently users log in—it's not quite a Metcalfe's Law curve, eyeballing it lines up with this estimate.

The obvious questions Nextdoor brings up are: why didn't a dominant social platform like Facebook or Twitter win in this kind of local news? Or, alternatively, why didn't a local-by-default product like Yelp, Foursquare/Swarm, or Google Maps create something similar to Nextdoor? In both cases, the answer is that Nextdoor focused on a model of interaction that focused on preexisting, geographically bound communities. Facebook's vision of a social network that mediates all relationships means that it has to maintain ties despite geographic distance; family members, college friends, and former neighbors are all valid friendships as far as the Facebook model is concerned. But on Nextdoor, their comments would be noise: they won't have any idea when construction will be finished on a nearby street, or what the deal is with a recent robbery. And location-based services like Yelp and Google Maps treat the location, not the person, as their fundamental unit.

Online social graphs tap into real-world social graphs, which lets them grow faster. A sufficiently dense social graph produces enough day-to-day news to keep a feed entertaining: marriages, breakups, vacations, pets, kids. But Nextdoor can take advantage of external content generation; anything that happens within the neighborhood can be news.

In one sense, Nextdoor took Facebook's earliest growth hack more seriously than Facebook did. Facebook grew because, on any given campus, it was ubiquitous almost as soon as it launched. A campus is a very self-contained environment; classes represent some forced socialization with other on-campus peers, and people attending a school will bump into each other fairly regularly. A typical neighborhood is less socially dense than, say, Harvard, but at least the default expectation is that people won't be there for just four years—and that if they leave, wherever they go next will probably constitute a neighborhood, too. Nextdoor's preexisting network is much weaker than the one Facebook started with, but also more ubiquitous; 62.7% of US high school graduates go to college, but 82.5% of Americans live in cities.

For both Nextdoor and other social platforms, the default question users have when they open the app is "What's going on?" That's a question that can be asked vaguely, out of boredom, or very specifically, out of intense curiosity about some otherwise confusing event. For example, my old neighborhood's Nextdoor is currently consumed with drama over a local restaurant owner who claims that a competing restaurant has hacked his Facebook page and tricked his employees into quitting; he's been posting signs in the restaurant window to this effect for several weeks. To someone walking down Bedford Avenue, this might be a pressing concern, or at least something they'd wonder about; for most people, it's totally irrelevant. For that specific category of question, Facebook's social graph of 259 million members in North America is less relevant than Nextdoor's 736-member Greenpoint network.

There's a broad sense in which Nextdoor is a very conservative social network. Most social networks are implicitly liberal (in the philosophical sense, not in the sense that they're necessarily aligned with a specific political party): they try to connect people around the world, and create a single global community where everyone is on a roughly equal playing field.

Nextdoor doesn't have a serious shot at shaking Facebook's market power, but it does illustrate that the opportunity set is always bigger than it looks. Facebook dominates social media, but with a particular paradigm, in which you have one externally-facing representation online, and as many of your interactions as possible are facets of it. Facebook has tried to make itself a more all-consuming app, through feature additions, a focus on groups, and more use of messenger. But Nextdoor was able to digitize a different set of social relations faster than Facebook could expand itself into them, and now it works as a standalone company.

Elsewhere

Ads and Unit Costs

AdExchanger has an interesting piece on some of the metrics Amazon offers merchants around ad ROI. It's fairly trivial to measure the immediate return on ad spend, but what's really being solved is a more complicated problem: how to allocate scarce dollars to ordering inventory, storing it, and selling it. If there's a low-turnover product, storage expense is relatively high, but if that product's sales can be juiced with ads, it may be a good deal. Amazon's medium-term incentive is to maximize seller profitability (their long-term incentive is to eat sellers' margins entirely, but over shorter time periods it's an iterated game, and Amazon's low cost of capital gives them a long-term outlook).

What's especially interesting about this is that it offers a peek into yet another reason that measured inflation has tended to be low. As more products get sold through metrics-driven ad campaigns, substitution gets easier; someone who spends 10% of revenue on Amazon ads can simply cut their marketing budget to zero when it's hard to source inventory, instead of raising prices. Many other retailers are offering internal ad products, for good reason, since it enables more price discrimination. This will make substitution within product categories easier, and will also give companies some flexibility to control demand. Measuring consumer prices over time assumes a stable consumption basket, but the more effective advertising gets, the less stable the consumption basket is.

Which Features Work

Twitter introduced a temporary tweets feature in November, and is now shutting it down due to low usage. Meanwhile, Clubhouse is adding direct messages in addition to its main audio product. Two points here:

Twitter was already designed for broadcasting, not narrowcasting; anything someone was reluctant to tweet but willing to fleet could be screenshotted and shared anyway. Clubhouse, by contrast, is all about a modest expectation of privacy: conversations can be recorded, but usually aren't, and private messages are a natural extension of this.

Twitter seems to have accelerated its pace of product launches in the last year or two. Killing fleets might be a positive example of this: a company that has a roster of upcoming products can be more willing to kill underperformers, especially when they take up valuable screen real estate.

Buy Now, Pay Later

For a few years, Apple has been in the business of providing consumer credit (not off its own balance sheet) for purchases of Apple products. On Tuesday, Bloomberg broke the story that Apple plans to offer this for other purchases made through Apple Pay, with Goldman Sachs making the loans. The Buy Now, Pay Later model is very much a creation of high customer acquisition costs in consumer credit, and this is an interesting arbitrage: it's a way to acquire users for Apple Pay, but also a way to make loans to a massive consumer base. Looking back at Apple's earlier credit decisions, it seems as if Apple was testing its underwriting abilities by lending to buyers of its hardware, and then, once it had good data, extending this to other kinds of borrowing.

One odd detail is that Apple won't be making the loans; Goldman Sachs will. Apple had almost $70bn in cash and securities on hand as of its latest quarterly report, and earlier this year it issued five-year debt at an interest rate of 0.7%; Apple is not exactly cash-constrained. But its software and services business mostly profits by being an intermediary between app users and app developers, not by building first-party products; this might be an extension of the same strategy, or Apple might be patiently waiting to see how profitable Goldman's loans are, and how much of that might accrue to Apple if future loans were on their books instead.

Tech Nationalism

Germany plans to ban a large porn site over its refusal to verify users' ages. Based on SimilarWeb data, the site in question gets 170 million visits from Germany each month, so this is a fairly significant decision. In some cases, like India's recent ban on MasterCard adding customers, it's easy to point to protectionism, but the German case is more purely about who can use the Internet for what reasons. Some countries' more political restrictions widen the Overton Window for less political, but no less effective, site bans.

Returns

The WSJ highlights the rise of return fraud ($), as scammers order products, claim not to have received them, and collect refunds. A fraud analysis company CEO claims that it's a big business: "Some people are making $20,000 a day doing this." This may be an exaggeration, but it is a growing one, and new fraud patterns tend to disproportionately benefit bigger companies; they have more datapoints for identifying fraudulent patterns, and they can cut off fraudsters' access to their sites. One set of solutions is behavioral:

Some retailers, including Finish Line and Under Armour Inc., now require customers to fill out an affidavit when items don’t arrive. The form asks questions such as whether customers checked with their neighbors to ensure the package wasn’t mistakenly dropped off at the wrong address. The goal is to slow down the refund process and deter bad actors, the retailers said.

A few industries have found similar angles; Lemonade asks customers to record a video explaining what happened that caused them to make a claim, both because the video can throw off useful signals and because making one is an inconvenience that reduces claims.

This is a case study in why a company like Affirm would want to buy a returns management product. Whatever the solution to fraud, it's easier at scale, so the return fraud-protection business is maximally efficient when it's spread out over as many retailers as possible, rather than being done in-house by individual companies with fewer resources and less data.