> My name is Julian

> This is my lifelog and digital playground

Multi-layered calendars

Traveling through time in three dimensions

Time is a curious thing. It’s a constantly flowing stream that can’t be paused, stopped, or repeated. We experience it, but we can’t control it. We can’t even touch or feel it.

To get a better grasp of this weird, intangible resource that governs everything around us, humanity has invented a variety of "time devices". These devices help us to plan and optimize how we spend our time. To make the most out of the here and now.

The most popular time device is the watch. A watch is a useful tool, but its functionality is limited to the present moment. It allows us to see time, but not to manage it. It only tells us the status quo.

Calendars, on the other hand, cover the entire spectrum of time. Past, present and future. They are the closest thing we have to a time machine. Calendars allow us to travel forward in time and see the future. More importantly, they allow us to change the future.

Changing the future means dedicating time to things that matter. It means allocating our most precious resource to activities with the highest expected return on investment.

You would expect technologists and entrepreneurs to be intensely focused on perfecting such a magical time travel device, but surprisingly, that has not been the case. Our digital calendars turned out to be just marginally better than their pen and paper predecessors. And since their release, neither Outlook nor Google Calendar have really changed in any meaningful way.

Isn’t it ironic that, of all things, it’s our time machines that are stuck in the past?

The essay at hand is an exploration of what calendars could be if they weren’t stuck in time. But before we discuss their future, we first need to analyze their present status and how they fit into the rest of the productivity stack.

Our productivity stack consists of four types of tools:

- Note-taking apps

To document and organize our thoughts - Email

To communicate with others - Task managers

To organize the things we need to get done - Calendars

To manage our time

The fact that we use four distinct tools suggests that note-taking, email, task management, and time management are four distinct activities. But when you look closer, you’ll realize that these activities are actually not that clear-cut. In fact, they all heavily overlap. Notes are just emails to your future self. Emails are just tasks. And tasks are just calendar events.

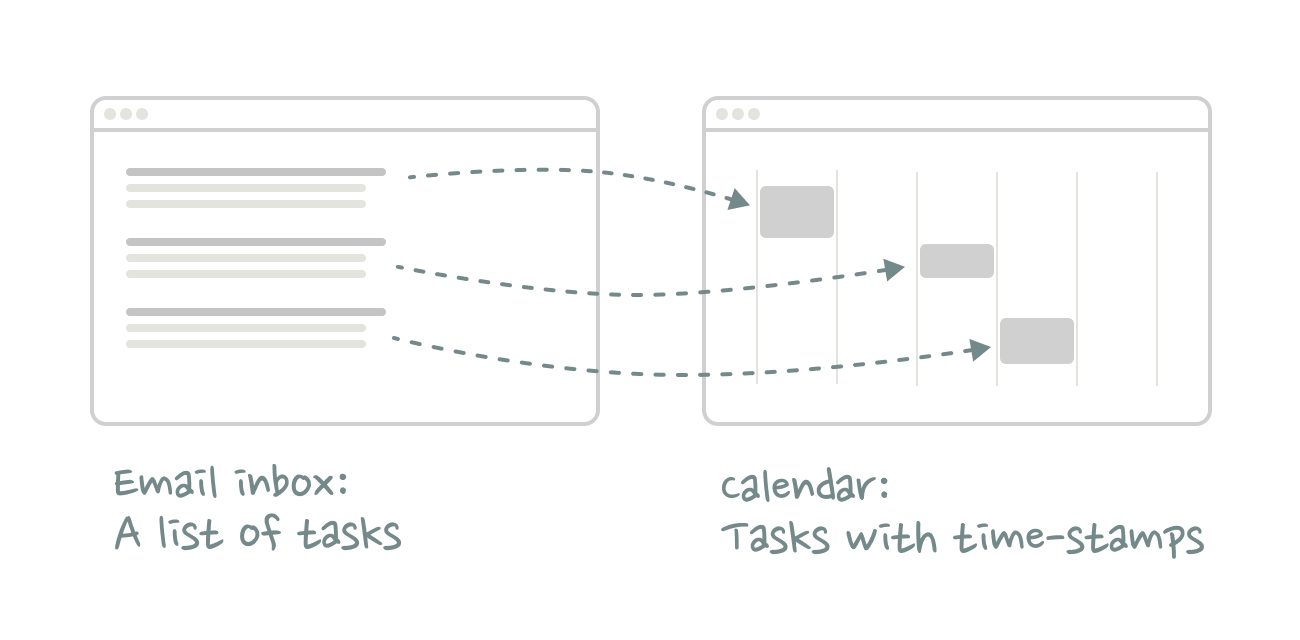

My personal workflow looks like this:

- I treat my email inbox as my primary task manager (and note-taking tool).

- Tasks are emails I receive from others or emails I send to myself.

- I snooze emails until the week I want to get them done.

- At the beginning of each week, I go through my email todo list and block time in my calendar for each task.

The email<>todo part of this workflow actually works reasonably well. Most of today’s email clients are built around the concept of Inbox Zero, which effectively turns your email inbox into a todo list with public write access.

The part we haven’t really figured out yet is the intersection between task managers and calendars.

Treating todos as calendar events is helpful because calendars introduce constraints. A calendar forces you to estimate how long each task will take and then find empty space for it on a 24 hours × 7 days grid, which is already cluttered with other things. It’s like playing Tetris with blocks of time.

So how do we get tasks into our calendars without awkwardly switching back and forth between two different apps that don’t talk to each other?

New productivity tools such as Amie are trying to solve this problem by natively inserting todo lists into the calendar experience. In Amie, every calendar event is a task that can be marked as done.

This approach is a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t go far enough. I agree that tasks should live in your calendar, but that doesn’t mean every calendar event should be a task. The way I see it, tasks are just one of many different types of calendar events. And just one of many different calendar layers.

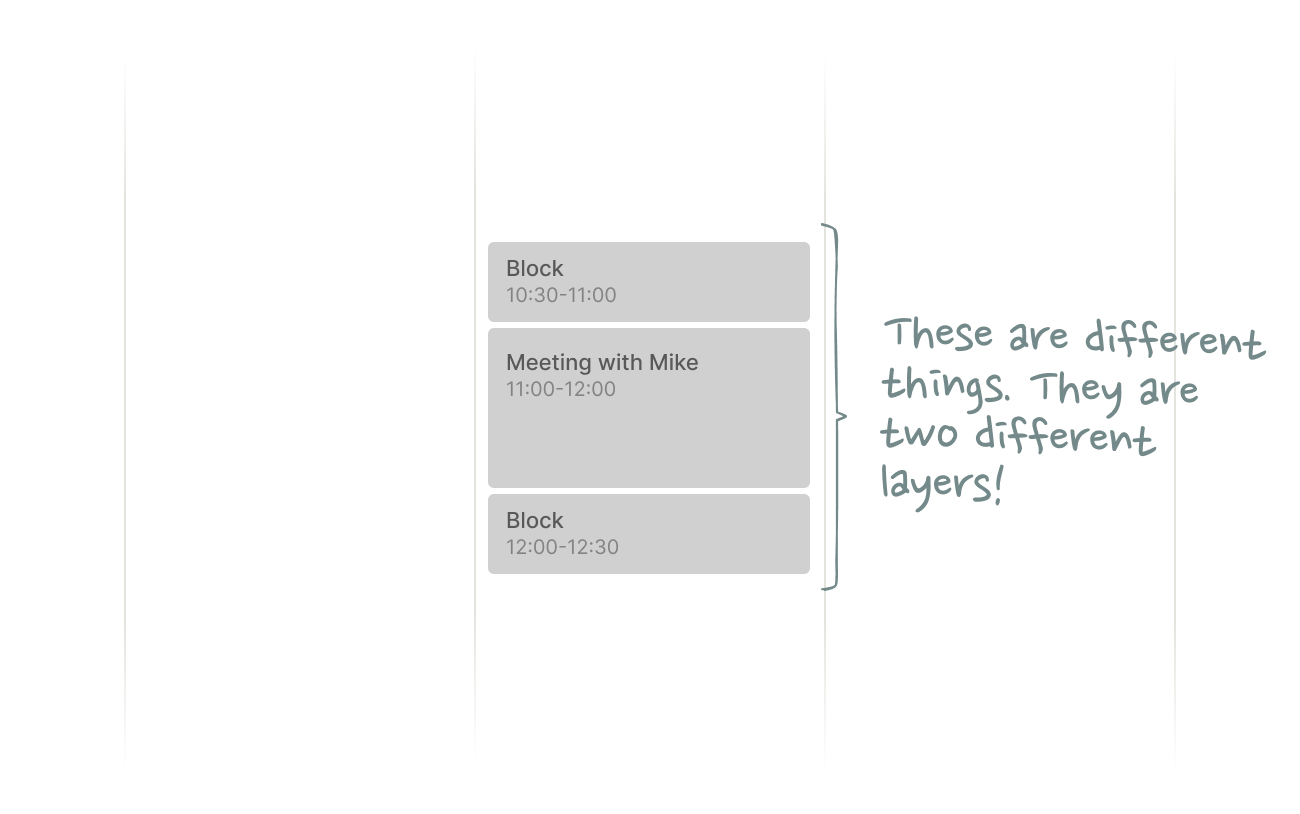

To make the concept of calendar layers a little more tangible, let’s look at a scenario that you have probably seen before:

What’s happening here?

1. You have a meeting with Mike

A meeting is a multiplayer calendar event. It is not the same as a task. It is simply a reminder for all meeting participants that their presence is required (or desired) at a specific time and place. There is no "to do" here apart from showing up on time.

2. You need to travel to and back from your meeting

To ensure that no other meetings are scheduled during those travel times, you added two "do not schedule" blocks (DNS). These are neither meetings nor tasks. Their only purpose is to avoid conflicts with other upcoming events.

The DNS blocks appear before and after the meeting, but what they really represent is one entire layer of time that stretches from 10:30 to 12:30. Your conversation with Mike is a meeting layer on top of your blocked time layer.

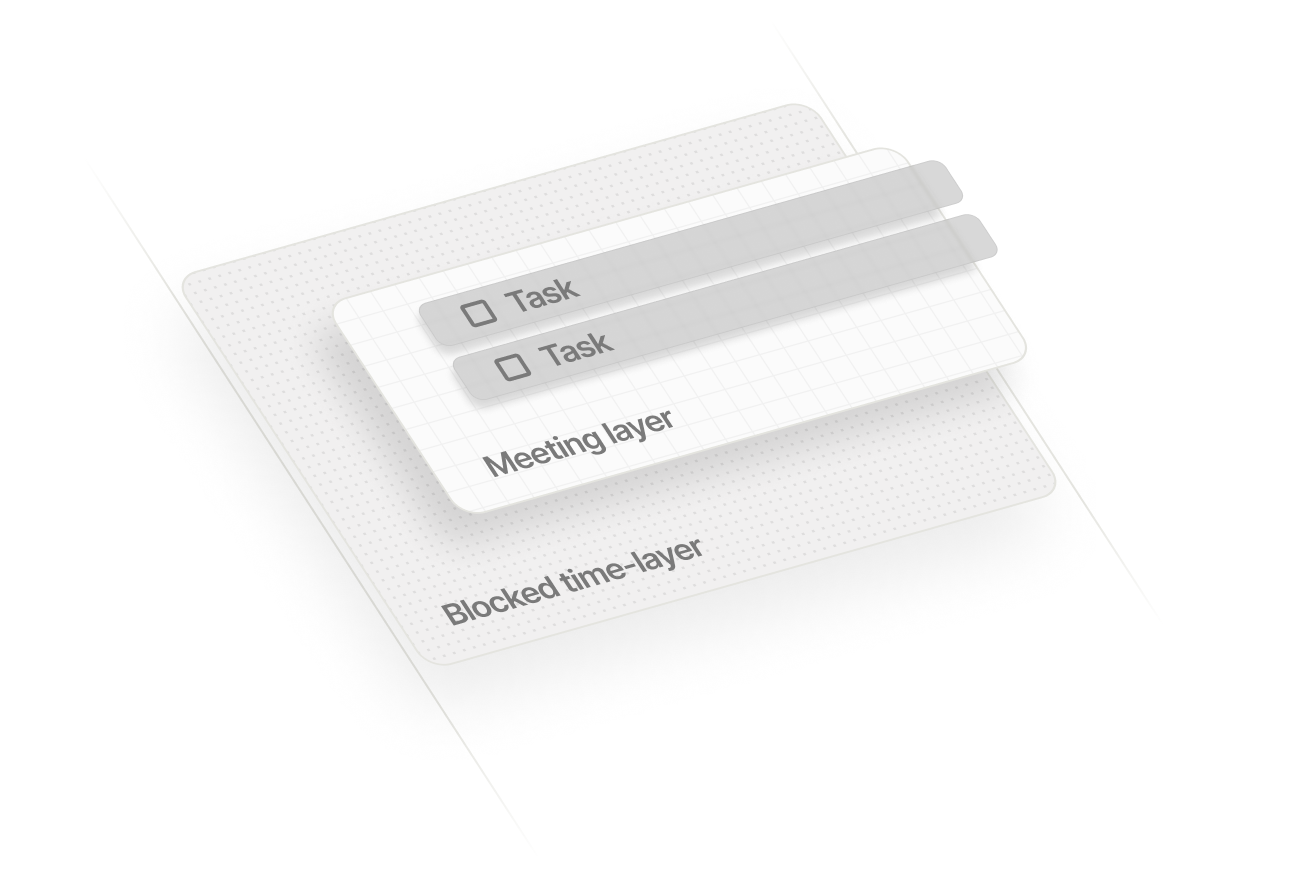

We tend to think of calendars as 2D grids with mutually exclusive blocks of time, but as this example shows, not all events automatically cancel each other out. Depending on their characteristics, they can be layered on top of each other. This means we manage time in three, not two, dimensions.

Let’s see if we can add another layer to the mix.

As discussed at the start of this chapter, neither blocked time nor meetings qualify as tasks — but what about talking points or agenda items that need to be covered in your meeting?

We are now looking at three different types of calendar events, each with their own unique set of properties. The problem is that our calendars treat all of these different events equally. They don’t natively differentiate between a task and a meeting even though they are two completely different things.

When I chatted with Cron founder Raphael Schaad about this issue, he pointed out another missing layer: Activities. An activity takes place for a prolonged period of time, but only requires your attention at certain points of it — not throughout.

Flights, for example, should be native calendar objects with their own unique attributes to highlight key moments such as boarding times or possible delays.

This gets us to an interesting question: If our calendars were able to support other types of calendar activities, what else could we map onto them?

A while ago, this mock-up appeared in my Twitter feed:

What’s so interesting about this idea is not just that it introduces another unique calendar layer, but that the data of this layer is rooted in the past. In contrast to traditional calendar events, all of these Spotify entries were created after they happened.

Something I never really noticed before is that we only use our calendars to look forward in time, never to reflect on things that happened in the past. That feels like a missed opportunity.

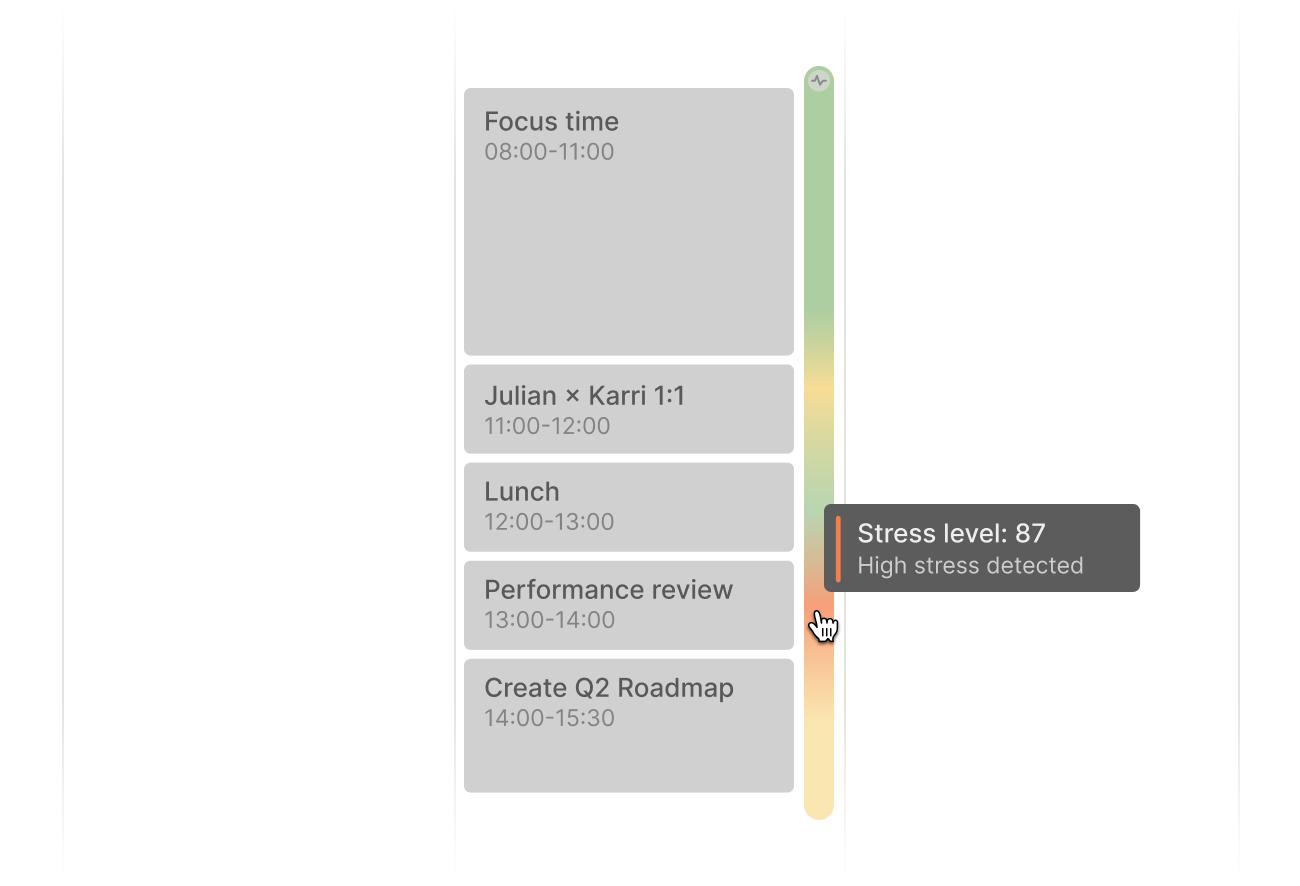

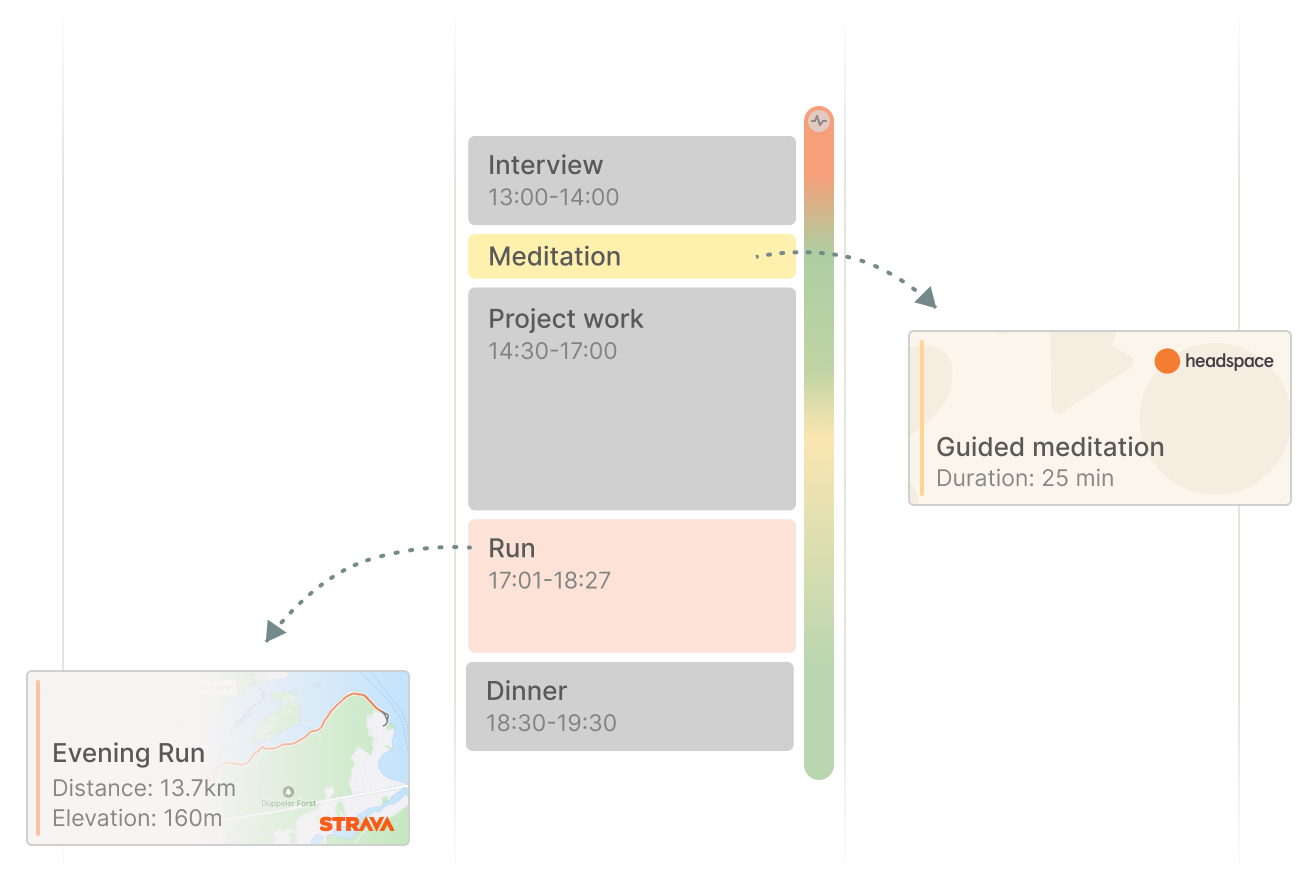

While a Spotify layer might seem more like a gimmick than a meaningful productivity hack, the idea of visualizing data from other applications in form of calendar events feels incredibly powerful. What if I could see health data alongside my work activities, for example?

My biggest gripe with almost all quantified self tools is that they are input-only devices. They are able to collect data, but unable to return any meaningful output. My Garmin watch can tell my current level of stress based on my heart-rate variability, but not what has caused that stress or how I can prevent it in the future. It lacks context.

Once I view the data alongside other events, however, things start to make more sense. Adding workouts or meditation sessions, for example, would give me even more context to understand (and manage) stress.

Sleep is another data layer that would make a lot more sense in my calendar than in a standalone app. I already block time in my calendar for sleep (mostly as a DNS-memo to coworkers in other time zones), so why not add sleep quality data directly to that calendar event?

This way I could plan my day ahead with a lot more accuracy. Fully recharged after a solid eight hours of sleep? Block more focus time. Lack of deep sleep? Add another coffee break to the agenda.

This example is particularly interesting because it leverages all of our calendar’s time travel capabilities. It allows us to shape the future by studying the past.

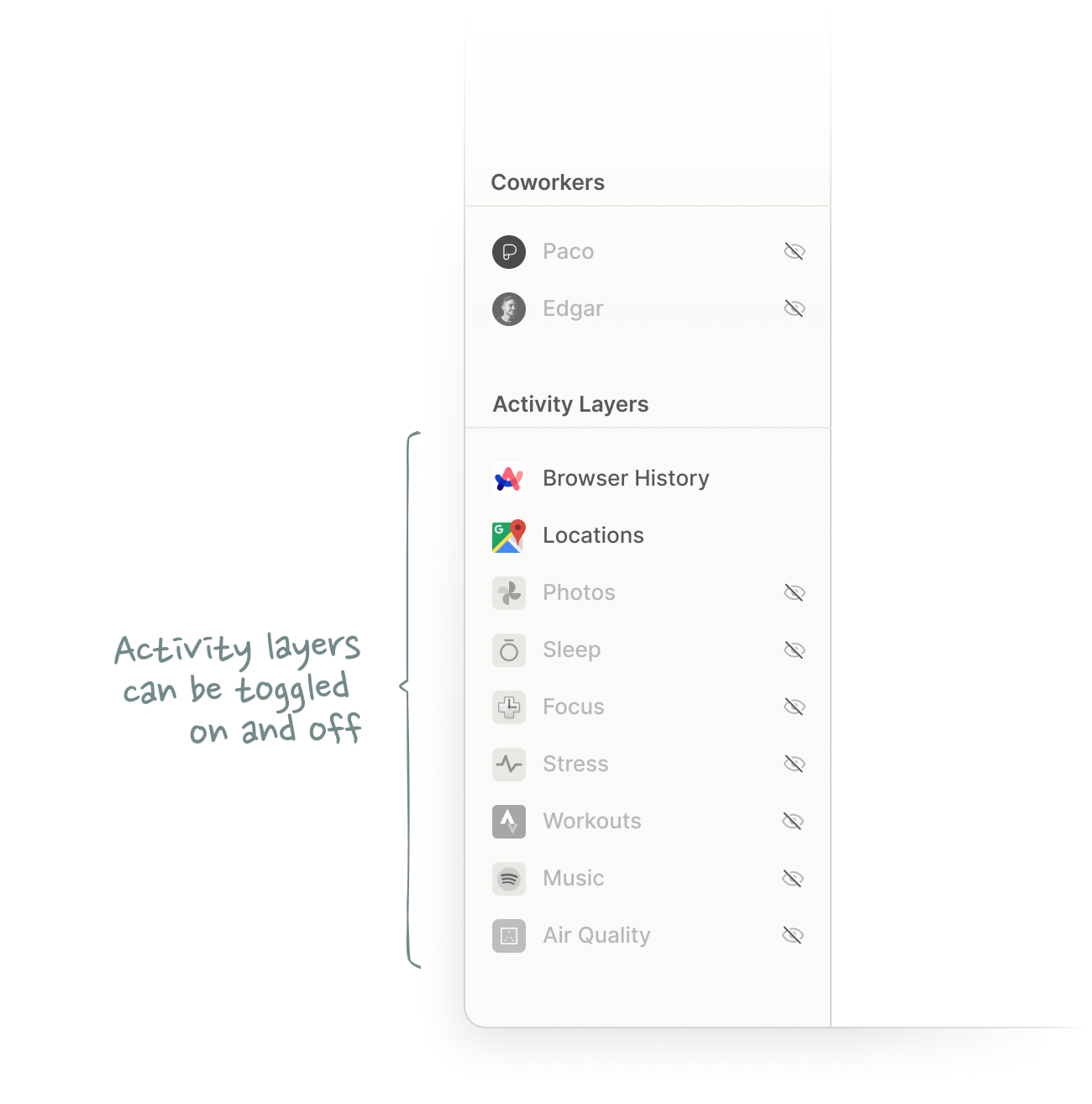

Once you start to see the calendar as a time machine that covers more than just future plans, you’ll realize that almost any activity could live in your calendar. As long as it has a time dimension, it can be visualized as a native calendar layer.

Most of these data layers are pretty meaningless in isolation; it’s only when we view them alongside each other that they unlock their value. Even a Spotify layer starts to make sense when you look at it in combination with stress data (which music calms me down?), productivity metrics (which music helps me focus?), or personal activities from the past (nostalgia).

The takeaway of this essay is twofold:

- Calendars should natively differentiate between different types of calendar events. Tasks, meetings, blocked time, and other activities should look and behave differently depending on their respective attributes.

- This would open the door for a virtually infinite amount of other use cases that could be integrated into the calendar experience in the form of unique calendar layers.

These changes would not just make the calendar a stronger center of gravity in the aforementioned productivity stack, but turn into an actual tool for thought, where time serves as the scaffolding for our future plans and our memory palaces of the past.

Thanks to Adam Waxman, Dennis Müller, Kevin Yien, Paco Coursey, Michael Karnjanaprakorn, and Raphael Schaad for reading drafts of this post.

× TIME: 2:10:12 pm

× LOCATION: Berlin, DE (52.5200081, 13.4049540)

× BEHAVIOR: thinking about calendars, thinking about tech