Master Plan - Dryden Brown (Bluebook Cities)

The CEO of Bluebook Cities discusses cities on Mars, social capital for pursuing hard problems, and Praxis—their new city in the cloud

Welcome to the 8th issue of Master Plan, a series of conversations with hard tech founders solving really difficult problems.

Dryden Brown is the CEO of Bluebook Cities, a company building affinity cities based on shared values and a common vision for the future.

Dryden introduces Praxis

I'm the co-founder and CEO of Bluebook Cities. We're building a new city with members of our society, Praxis.

Praxis is a society of founders, engineers, artists, researchers, and young aspirants building towards a shared vision for the future through the pursuit of heroic projects.

Our values dictate our desired future. If we want to develop a heroic vision of the future and solve the stagnation problem, we need to live with people who share our values. And to the extent that you can formulate a clear vision for the future, living in a community that shares your values makes you much more likely to build it.

We want to return to the future that people expected in the early 20th century and solve the stagnation problem.

The first step of this process is to build communities that are founded on shared values. So at Praxis, we’re building a community founded on shared values, through online and in-person events. And simultaneously, we’re also working on acquiring a beautiful piece of land and having everyone move there together.

We named it Praxis (process), as opposed to theory. The notion is that there’s a ton of really interesting theory pertaining to getting back to the future. For example, Thiel exists at the meta-level where he describes the playing field and the problems that exist towards getting back to the future. But we think putting those ideas into practice is what we need to do at this point.

Shared values determine which sort of future you want to pursue. There are certainly a bunch of other important factors, like having really talented people, having a good education system, being in a climate conducive to productive work (a Mediterranean climate is ideal)

I think that having physical spaces, so people can develop tight relationships, become friends, trust each other, and so forth, is important. It’s important to have a physical Silicon Valley, as opposed to just "Silicon Valley in the cloud."

The biggest problem in current cities is that the people who run them don’t have incentives that are clearly linked to the welfare of the average resident of the city. Whereas if you actually own the city, your main incentive is to get people to move to that city.

Heroic Projects and Paths to Immortality

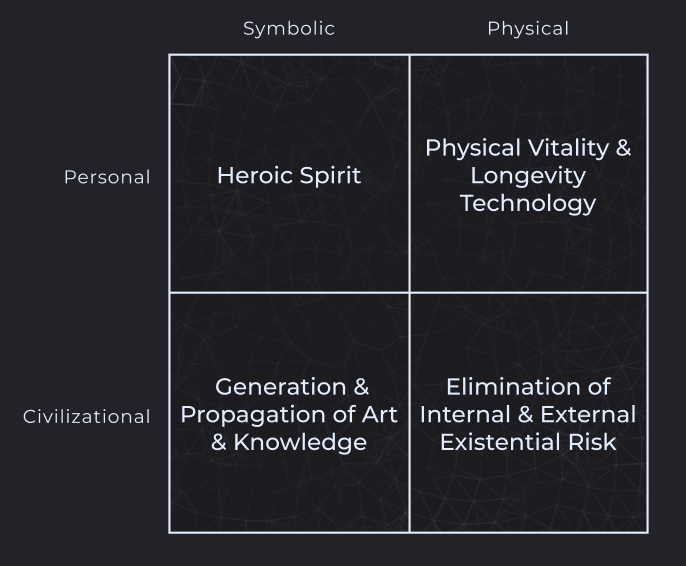

The core idea of our community, Praxis, is that our purpose is to pursue immortality. And immortality is a very generative concept, which means there are a bunch of ways you can think of immortality. The most mundane way to think about it is physical immortality of yourself, where you’re personally living forever.

But there’s also this ancient tradition of symbolic immortality, which is the pursuit of heroism or eternal glory in the minds of men. We all have a deep biological impulse to avoid death. If you want to use inversion to solve the problem of avoiding death, the answer is to pursue immortality.

We live in this sort of constructed symbolic world, and the way this pursuit of immortality and avoidance of death is mediated in our symbolic world is through heroic action, like inventing new technology or creating beautiful art.

But there’s also civilizational immortality, which is quite important on both the surface and in the symbolic sense. Just like physical immortality, civilizational mortality is also somewhat mundane yet super exciting. For example, it’s about solving the existential single point of failure problem that Elon’s working on by getting to Mars and getting out into the stars and persisting into eternity.

Praxis Brain—intellectual scaffolding for heroic projects

All societies have traditions of knowledge they’re based on that comprise their operating procedures. In Western democracy, there are assumptions about human nature that inform our political systems. For example, human equality and the malleability of human nature. There are foundational ideas like those that inform how we operate as a society.

And of course, there’s a massive canon of Western literature, philosophy, and scientific work. I think all societies need their own tradition of knowledge that represents the lens of the values through which they view the world. So for us, we’re working on building something like a personal Wikipedia that serves as intellectual scaffolding to support our vision for the future.

The notion is we’re saying that the world is a certain way, and if we do X, then we get to a world that’s more in line with our values. Thinking in this way requires forming a bunch of assumptions. We’re building out an intellectual scaffolding to make those assumptions explicit. That way, we’ll have something useful towards organizing human capital in a way that makes it easier to realize our vision of the future.

Scaling a city in the cloud

With many online communities, the quality drops significantly once you hit a certain threshold of members. Praxis scales and maintains quality because everyone in the community is working on a heroic project. These people are not the type of people that should be spending time in a large group chat. The plan isn’t to build a 2000-person Slack or Discord.

So we have events that are as small as possible on a weekly basis. What we do is we run these small 8-person weekly calls where we talk about the projects that we’re working on (our heroic projects) or our exploratory process looking for a project. And the core idea here is to create friendships between the members and strong bonds—a high-trust place where people want to help each other, make introductions, and spend time with one another.

We also have the Praxis Brain, where that’s split up into multiple domains. One domain we launched recently is statecraft, where we have a group of people working on sketching out the future of statecraft and doing some theory work, collecting a ton of interesting documents, synthesizing them, and running seminars.

In terms of collaborative projects, it’s highly balkanized in Praxis Brain. And then in terms of purely social events, they’re quite small. If you’re running an online community and you don’t have resources, then it’s really hard to do because it takes an enormous amount of time. We have a business model that can support an excess amount of resources being spent on making the community experience super compelling at scale.

Learning to build cities

The best part about working on affinity cities is just the scope of the impact that one can have. You could help millions and millions of people build better lives for themselves and for their families by creating institutions and a social environment that enables them to do build interesting businesses and so forth.

However, you have to be doing a lot of different things simultaneously in any combination. What we’re doing is unprecedented. Just like when you’re doing anything new, it’s quite hard.

I read a lot. I read a lot of old books and I talk to interesting people, most of whom I meet on Twitter. And I just sit and think a lot. It doesn’t sound super exciting, but I take significantly more time than most other people running startups to just sit with ideas and think deeply about them.

When asking for advice, I think the audacity of the idea is attractive to some people and that’s what makes them want to help. The idea of building a completely new city is a little weird. And I think most people are working on ideas that aren’t quite "out there." So what we’re doing piques people’s interests. I just think about a bunch of weird interesting things that many people have come across and that they might find engaging.

But when you’re working on something like this, you could be working on governance, real estate, etc. Often you’re building technology to do demand aggregation. You have to raise money in creative ways. So you’re just solving a bunch of new problems, and you end up learning a bunch of old trades along the way.

Finding the ideal government partner

When partnering with governments, there’s a lot of bureaucracy and paperwork you just have to accept. Generally, you want to work with governments that have a really strong incentive to partner with you. You need a very strong value proposition for the partnership to really make sense.

For example, what we’re offering governments is a totally unprecedented human capital transfer. It’s like a slice of Silicon Valley that’s been dislodged due to COVID. You might never have the opportunity to pull in as many talented people at once ever again. So for governments, there’s a strong incentive to move quickly, at least in this one instance.

The governments we’ve been speaking to run smaller countries. They’re more nimble. Sure, governments aren’t able to make decisions as quickly as startups, but I do find ones that really want to get things done.

Building the team that builds a city

When we’re hiring people, what we look for depends on the role. There are a few positions where we want to hire fairly veteran, sophisticated people, particularly in governance and on the real estate side.

For roles on the design side, the demand aggregation side, or the technology side, it’s probably a bit more akin to a traditional startup where we want hyper-focused super-smart undiscovered talent.

Ideally, we find people who are into working on really weird projects and are really bright, and I think Twitter is a good mechanism for finding some of these people. I’ve sort of cultivated my Twitter such that I have a bunch of these people who see my stuff and that’s been quite useful.

Why more people aren’t doing hard stuff

It’s a complex problem. Basically, it’s about creating a social climate where people feel like their ambitious ideas are actually achievable. Some of it depends on having more people like Elon Musk—more mimetic models that show people that there’s another way.

Even having just one person doing crazy hard stuff—like Blake Scholl of Boom—makes what Elon’s doing feel a little bit less singular. When you see Boom, it makes everything look a little bit more accessible. Presumably, Blake is very smart, but it still makes working on those types of problems feel more achievable than if it were just Elon standing alone.

I think convincing a singular person, like a friend, to work on their most ambitious company idea will also convince you to do those things. And if we can get more people convincing each other to do hard things, many people will have success, and then there’ll be these massive spillover effects where you start to see 20 other companies that are insanely ambitious start to work. And once we reach that point, it starts to feel more normal that this is a path that one can pursue.

SaaS companies are really working right now. They’re discovering much bigger markets than people thought they would, and the margins are quite good. So there are really strong economic incentives not to do atoms companies or companies that build physical things. But the pendulum starts to swing too far at a certain point, and then eventually the economics will make sense to pursue physical products and companies to the extent that a social climate exists that prizes this and gives those people access to social capital for pursuing those kinds of projects because they really matter. That unlocks a ton of these types of startups.

If I were to distill it down, we need to create a culture that gives people access to social capital for pursuing hard, ambitious problems. Because otherwise, software companies will always win because the economics are simply better.

Cities on Mars

I find space to be super compelling. I’d probably just bone up on that and figure out how I could do something meaningful in space, but I don’t have any ideas as to what exactly to do.

The whole affinity city process transfers over to building cities on Mars. When we reach Mars, we’re gonna have to figure out a lot of problems like:

How are those cities going to be governed?

How do we coordinate?

How do we solve the collective action problem to get people to commit to going?

I would go to Mars. It sounds pretty sweet. But how would you make it appealing to some base number of people? You’d probably set it up like a bunch of research teams.

The demand aggregation problem, the collective action problem, and governance problems definitely transfer over from Earth to Mars. Construction and building things on Martian soil might be different, but I would be down to go there and build it in 50 years or so.

Bluebook Cities’ Master Plan

Build a city in the cloud populated by amazing people working towards a shared vision for the future

Partner with a thoughtful government to build a new city

Grow the city and build the future humanity deserves, together

The core idea here is that cities today have a very weak social fabric. For example, you might know the name of your neighbor in your apartment building, but it’s unlikely you have anything in common with them. Cities are currently organized on a purely economic basis.

Instead of building cities as labor markets, we want to build cities organized around shared values. So what we’re doing is we’re organizing a massive group of people online that share values in this community, Praxis. And we’d also like to live with one another through these shared values and interests.

And then once we’ve created the massive online community, our next step is to go and talk to a bunch of different governments that have reached out to us expressing interest in hosting a city comprised of people in this community and brokering a deal where we occupy a piece of land and create a totally unprecedented human capital transfer, where we bring a ton of the smartest people in the world to their country and build infrastructure and buildings at the scale of a small college for the first batch of residents.

So we’ll bring people over who find that vision to be compelling. The real sort of compelling incentive to become one of our first presidents is land ownership. Manhattan’s land value is at $1.75 trillion. Manhattan is worth significantly more than Amazon. The notion is if you’re a founding resident, you can own land in a new city at a very low base cost. And we could potentially create a ton of enterprise value and increase the land value very significantly in a relatively short period of time, assuming it’s as great as we think it’s gonna be for people to want to move there.

Thanks for reading! You can follow Dryden on Twitter @drydenwtbrown if you haven’t already. And if you’ve learned something from this newsletter, try sharing it with your friends.

If you’d like to read more about building ambitious companies, sign up here. You’ll learn how founders go from a crazy idea, to hiring a team, and solid execution.

For any questions, feedback, or requests, send them to me via Twitter.