Mapping the Effects of California's Prop 13

40 years ago this summer, voters in California approved Proposition 13, a law that initiated sweeping changes to the California property tax system and permanently re-shaped the dynamics of property ownership in the state. Prop 13 is known in California and beyond as the rule that protects low-income, elderly property owners from being priced out of their own neighborhoods. It also means that recent home buyers provide an outsized proportion of local taxes, often paying taxes magnitudes higher than their neighbor for almost the exact same house.

These effects are well known. But given the complexity and scale of the issue, it has been hard to visualize how extreme the disparities are—until now. New maps from Urban3’s analysis in the Golden State visualize the effects across three towns from a micro to regional level.

What’s Prop 13?

But first, what exactly is Prop 13?

200 years after Americans declared themselves free from taxation without representation, California was in the midst of its own taxpayer revolt. Creeping inflation and a population influx spurred a wave of populist sentiment centering on the American Dream of property ownership. Retired businessman Howard "Mad as Hell" Jarvis emerged as the leader of the movement, gaining enough popular support to put a referendum on the ballot to dramatically limit property taxes, despite the ensuing budget cuts to education and public services. The ballot initiative passed by a 30-point margin, and Prop 13 became law.

Prop 13 amended California’s constitution to assess property taxes at 1% of a property’s purchase price with increases limited to less than a 2% annually in assessed value. If the property is sold, its value is assessed at sale price. The rule’s reach was later expanded by Propositions 58 and 193 to exclude heirs from reassessment as well. Critically, Prop 13 treats individuals and commercial entities identically.

What’s wrong with Prop 13?

So what's the matter with prop 13? For one, it's easy to exploit. In a commercial real estate transaction, for instance, a building owned by an LLC can avoid reassessment by shifting proportional individual ownership while never technically changing hands. This freezes the tax rates in time, sometimes to pre-1976 levels. In his Revisionist History podcast series, Malcolm Gladwell discovered that, as a result, Los Angeles taxpayers subsidize the LA Country Club by $89.9 million dollars a year.

Another famous example is Disneyland, which pays five cents per square foot of land — eight times less than the average California homeowner. When longtime property owners pay far less than market value, the brunt of property taxation falls squarely on new homeowners and anyone who relocates to or within the state.

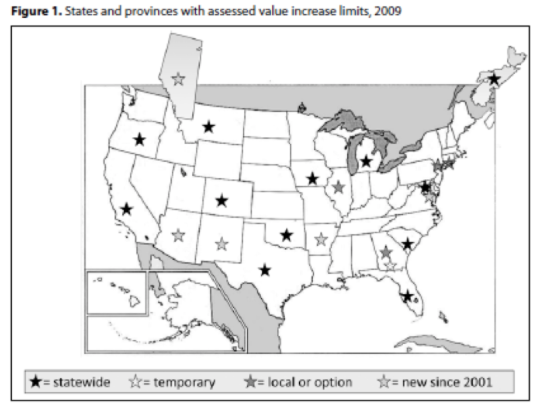

(Source: Michael Pagano, from the Urban3 archives)

Rent control is one of the few policies that most economists agree is a bad idea, since it artificially manipulates the housing market. In that vein, Prop 13-like laws are even worse, because they pass the benefits of tax policy on to long-time landlords and developers who can reap the benefits in perpetuity—and their children can, too, thanks to inheritance stipulations.

So what does this mean for the city’s coffers? When it comes to analyzing the effects of property taxation on city finances and development patterns, Urban3 Principal Joe Minicozzi is an expert. He views California as a particularly strange case, since Prop 13 and other referendum-backed propositions have scrambled the economics of land valuation and taxation beyond recognition.

"All of the policies are well intended, but they yield performance failure in the economics of cities," Minicozzi says. "If you suppress revenue streams when they are not connected to cost, there will always be a failure in the math. If a deal like Prop 13 sounds too good to be true, it probably is, because the cost of your community is not fixed. The cost of government isn’t restricted at 2% per year. Do you want your teachers to get a raise of only 2% per year? It’s shortsighted."

Minicozzi also wonders about the dangers of instant gratification. Prop 13 was beneficial when it passed because it allowed taxpayers to collectively and immediately address a perceived crisis. But the consequences for the state budget have been long-lasting. As architect and planner Andres Duany puts it, "codes spread like oil slicks"—and when accountability is dispersed to the public, constitutional amendments can spread just as fast. Soon after it passed, Prop 13-like laws started to spread across North America before the full ramifications of the policy were even realized.

Santa Rosa

Prop 13-style laws manifest themselves spatially in various ways. The following visualizations from different California cities shed light on just a few.

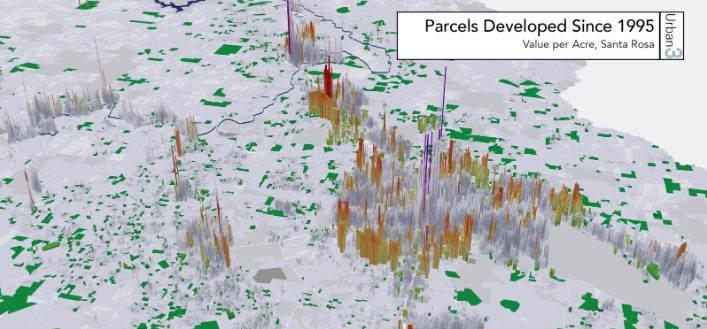

For instance, Prop 13 allows older Californians to stay in their homes longer—but what if empty-nesters want to downsize? Since Prop 13 discourages homeowners from moving, it increases the need to build more homes for newcomers—and to do it as quickly and cheaply as possible. Analysis in Santa Rosa shows that the majority of parcels developed since 1995 are auto-oriented developments at the town’s edges.

This map illustrates tax value per acre for each parcel in Santa Rosa. Taller spikes on the map have a higher value per acre, while smaller parcels have a lower value. Colored spikes on the map were built after 1995. Since the burden falls on these properties to generate the bulk of tax revenue for the city, Prop 13 acts as yet another factor that incentivizes and subsidizes the Suburban Experiment.

Redlands

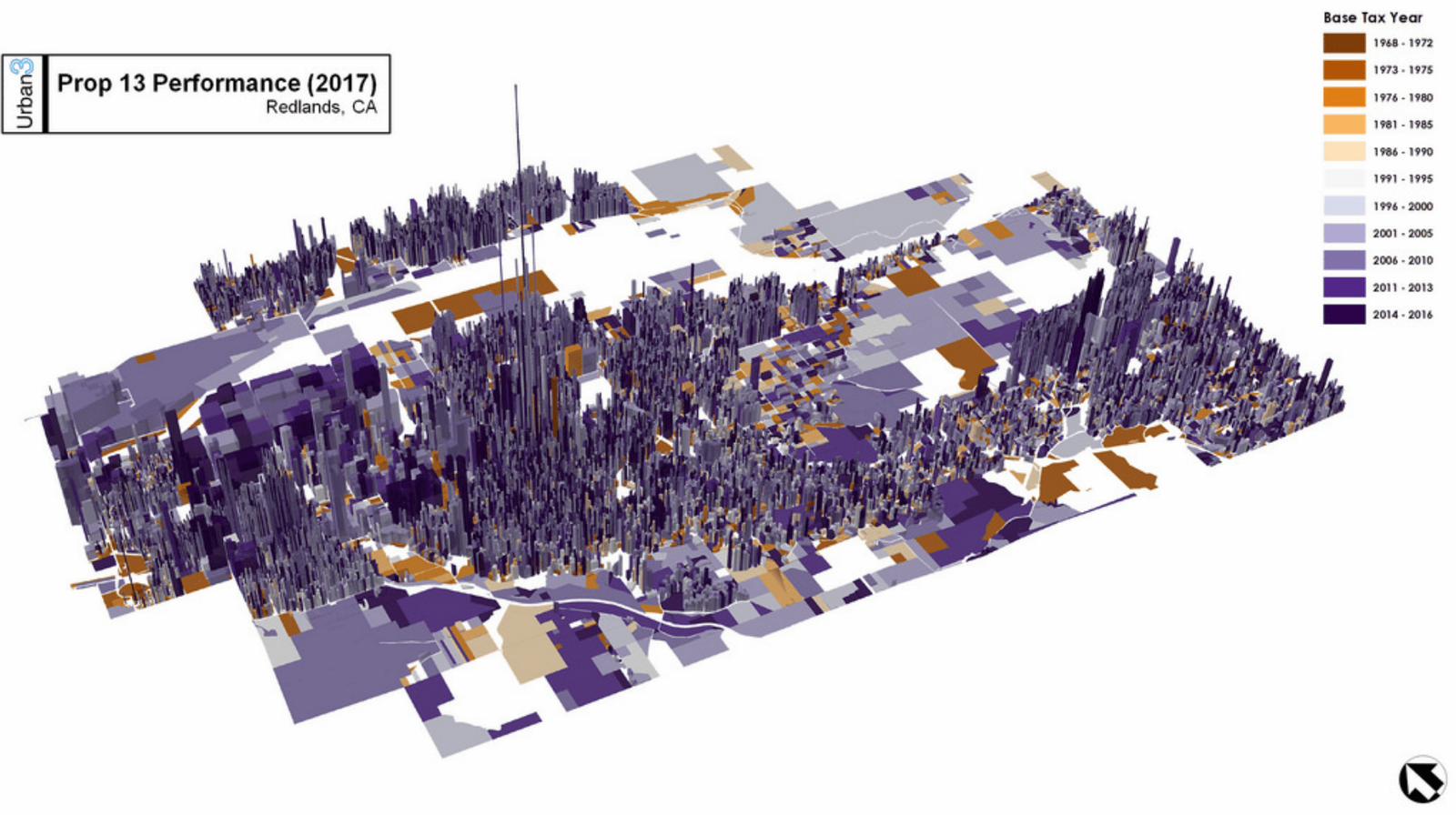

In this data visualization of Redlands, CA, height represents tax value per acre while color depicts the base tax year. Recently transacted property is much taller, while the low-lying properties colored brown contribute the least to the tax base.

Notice the stark differences in height within the same neighborhood or block. The properties depicted here are not particularly different in terms of age, style, or quality. What differs is the year in which they changed hands.

Davis

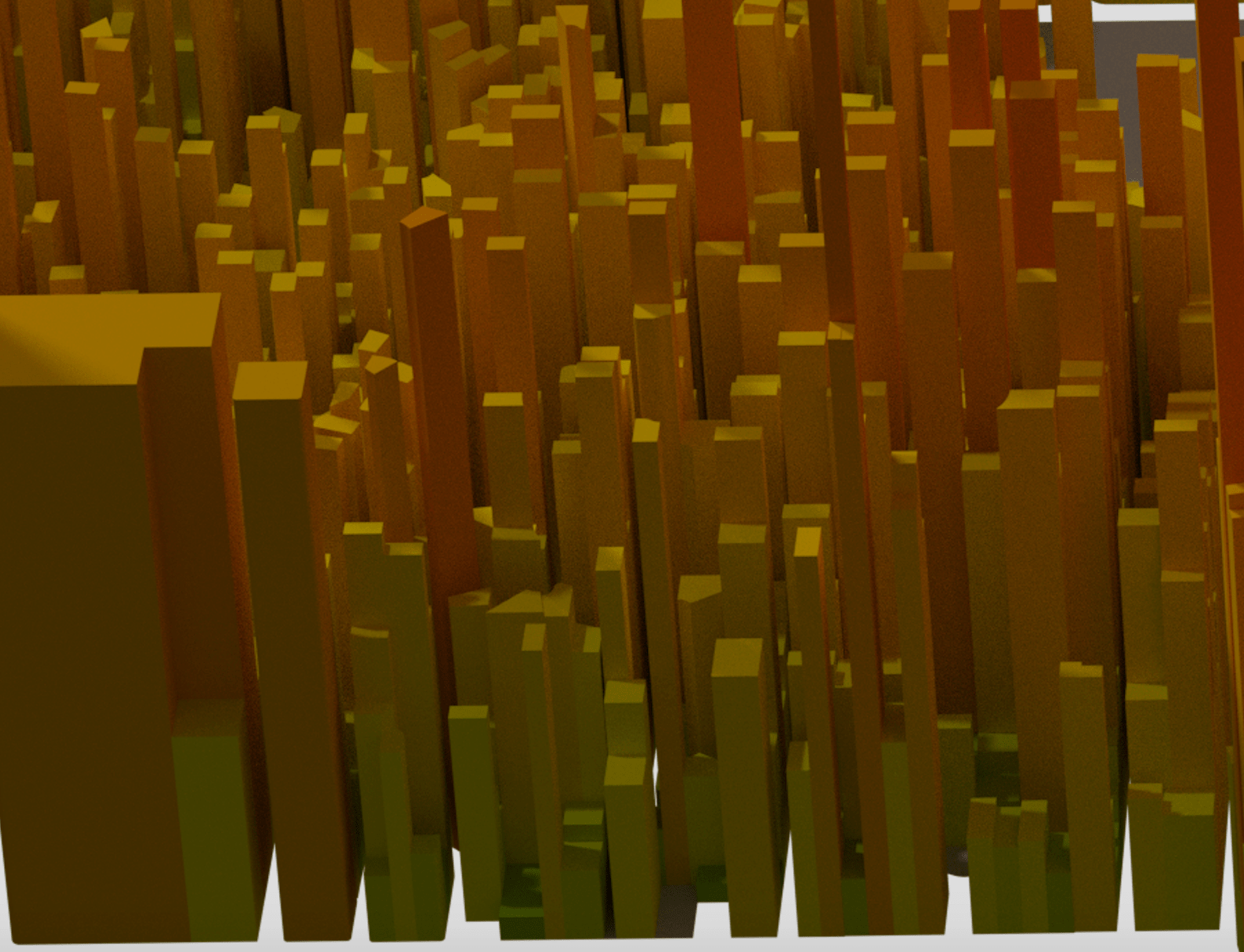

This close-up view of a residential neighborhood in Davis shows how properties directly adjoining one another can vary wildly in assessed taxable value. These houses are similar in form and size, and their market values are all roughly comparable. Unlike the previous maps, though, this map has no color-coding by base tax year, and height only represents property tax rates.

You are seeing in excruciating detail how Prop 13 allows one homeowner to pay taxes that literally tower over their next-door neighbor’s rate. Urban3 has produced over a hundred of these value per acre maps, and they have observed no place but California where these startling inequities are codified more clearly.

---

Jerry Brown was the Governor who first presided over Prop 13, and he is now finishing his second tenure in office after a 36-year break. He initially opposed the measure with all the political capital he could muster, but now he resignedly claims it to be "a sacred doctrine that should never be questioned."

At Strong Towns, we believe in questioning our laws if they demonstrate a misalignment between costs and services. The negative effects of Prop 13 can be mitigated incrementally to address its original intentions while closing loopholes. Here are just two measures that could address the system’s many insufficiencies over time:

Remove Prop 13 protections for corporations with a Split Roll. This measure splits the tax roll by distinguishing between residential and commercial property, finally forcing established businesses to pay their fair share.

Remove Prop 13 protections for vacation homes and other non-primary residences. This stays true to Jarvis’ word, preventing people from being taxed out of their homes, while restoring sensible tax assessments for a person’s second, third or fourth homes.

Let’s let Granny keep her home without subsidizing corporations, encouraging irresponsible development patterns, and abstracting land use economics even further. Furthermore, let’s not rubber-stamp policies without thinking through the long-term effects.

(All graphics courtesy of Urban3.)